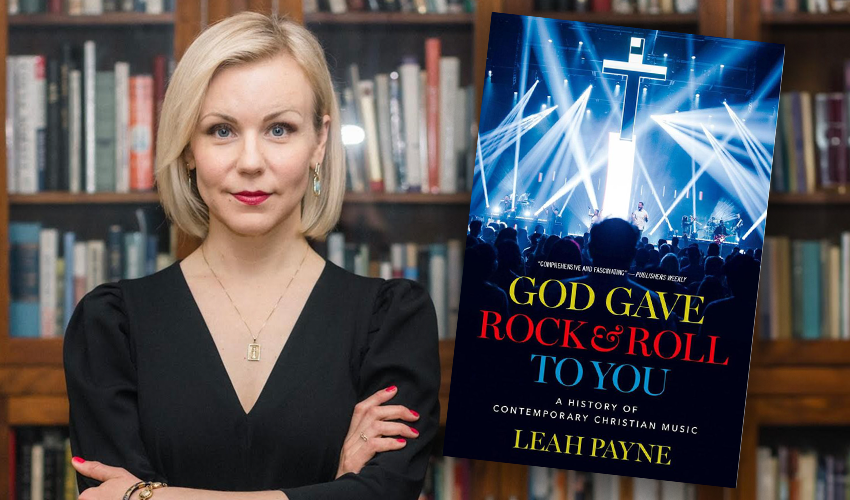

Review: God Gave Rock and Roll to You, Leah Payne, Oxford University Press

You could pick from any number of artists to illustrate the bumpy ride of Contemporary Christian Music (CCM). Jennifer Knapp was a darling of the scene in the early 2000s. Her unusually mature debut album matched the usual themes of sin and salvation to an alt-country sound. But as an adult convert, she was perplexed by CCM’s obsessions with abstinence and Republican politics, and, later, when she came out as lesbian, she was dropped like a hot potato, even though she never renounced her faith.

Contrast Knapp with Amy Grant. Age to Age was the first platinum CCM record, and Grant pioneered crossover into the mainstream, along the way igniting debate that now seems quaint, about her dress, dancing and admission of once having sunbathed nude. She divorced in the 1990s, creating a short-lived scandal, but negotiated through this and remains a nostalgic favourite.

Grant’s success nevertheless raised questions central to the genre and to the narrative of Leah Payne’s history: which moral issues would be prominent, whether CCM was church music or evangelistic, whether it was conservative or would retain some of the radicalism of the Jesus People music of the 1970s. Such questions were never really resolved, except that there were always those who argued for a narrow definition of CCM, and others who saw it as a broad church.

Rock’n’roll was always closely associated with teenage rebellion, so the mix of rock and God confused many. Some tried, not always successfully, to flip the debate, arguing that Jesus was the ultimate rebel, and modern Christians were rebelling against a teen culture that promoted promiscuity and drugs. But there would always be an identity crisis element within CCM, which mainstream rock critics were quick to point out and make fun of.

Most buyers of CCM were actually ‘suburban, middle-to-upper-middle-class, straight, white’ mothers. While many adults who had listened to CCM back in their teens later praised the positive effect of the music, there was always the taint that this was about as (un)cool as your mother curating your wardrobe.

Much of CCM was centred in the evangelical churches, meaning that it tended to be politically conservative, most obvious in the likes of serial Republican inauguration performer and Ken to Amy Grant’s Barbie (as Payne describes him), Michael W Smith, who is a friend of George W Bush and supporter of Trump. Combined with a targeting of teen audiences, this meant that there was a focus within CCM on sexual morality and eschatology, rather than more Leftist issues such as poverty or racism. While Smith sang naively about being ‘colour blind’, some Black Americans saw this as further marginalisation. Payne traces a prominent white streak through CCM right back to Southern revivalist churches of the early twentieth century, which effectively created Gospel music for white people.

But there is another side to CCM that emerged in the 90s, centred on the West Coast of the US rather than conservative Nashville. Punk, metal and alternative bands on labels such as Tooth and Nail evangelised to various degrees, but they were far less likely to vote Republican, or be approved of by listeners’ mothers. Tooth and Nail was an easier-going outlet for the likes of Starflyer 59’s Jason Martin, who attended church but whose songs weren’t obviously Christian. Outliers such as Mark Heard and Pedro the Lion’s David Bazan pushed artistic boundaries, while DC Talk’s Kevin Max renounced his former conservatism and, along with the likes of Derek Webb, criticised CCM’s cosiness with the Republican party.

CCM was always promoted as about evangelism, but Payne highlights that artists were largely preaching to the choir and keeping teen churchgoers, churchgoers. Critics complained about this safe aspect of CCM, perhaps missing the point that it had become an industry, like the fast-food industry.

The increasingly commercial turn of CCM meant it suffered more than most from the shake-up of the music industry through the internet and digital music. CCM never bounced back from the highs of the 1990s. CCM also reflected the increasing divisions on party lines in America. One result of all this was that worship music became the leading sub-genre. Rockers returned to the underground, while those who had the experience of penning worship music survived and thrived.

Nowadays, CCM has almost come full circle, with megachurch worship music dominating. There was at one stage a New Calvinist trend, with the likes of preacher Mark Driscoll promoting hyper-conservative gender politics, but victory goes to the Pentecostals, whose music is ubiquitous across even denominations that don’t necessarily agree with the underlying (individualistic) theologies. A future challenge for churches will be encouraging local, distinct, theologically deep worship music that doesn’t follow the trend of global homogenisation.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.