The Apollo Chronicles, Brandon Brown, Oxford.

Reaching for the Moon, Roger Launius, Yale.

Putting aside for a moment the ethical issue of whether it was worth all the money, the Moon landing was a technological triumph, as Brandon Brown’s history concentrating on the behind-the-scenes work shows. The 1960s was a time of optimism about, even quasi-religious faith in, technology, even if John F Kennedy’s speech outlining the goal of a Moon landing made scientists ‘incredulous’. Making the necessary leaps in rocketry, new spacecraft design and new computer technologies for navigation and communications was a feat.

Attempts at space-going rockets were initially unsuccessful and something of a joke. Trying to catch up with the Soviets and their launch of Sputnik, attempts to put a US satellite in orbit ended in failure and the press dubbed the debacle ‘Kaputnik’. It is said that rockets kept exploding until one didn’t, and then NASA put astronauts on top of the next one. This is not quite the truth but it comes near to describing the pushing of limits.

Moon rockets needed to be many times more powerful than those that existed at the start of the 1960s. Scientists initially didn’t think it could be done. Aside from the pure power, they had to make pumps that handled extreme heat and cold in proximity. They needed to keep the fire and fuel apart until the right moments. They battled minute cracks, seal failures and stuttering burns that rattled the rockets to pieces.

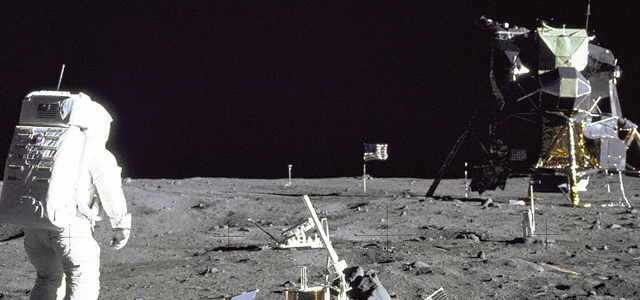

How to get out of the Earth’s atmosphere was only the first problem. The astronauts needed to get to the Moon’s surface, then back into orbit, then back through the Earth’s atmosphere. Spacecraft were needed that kept astronauts safe and coped with the extreme heat and cold of outer space. NASA contemplated a large craft that would travel to and land on the Moon and return, something like the sleek vehicles depicted in sci fi books and films. But the safer and more economical option was modular – lumpy and gangly, but it did the job.

There was the tricky maths of trajectories, where miscalculation could result in crashing or floating off into space. One mission re-entry vehicle landed hundreds of miles off-course because NASA engineers forgot to factor in the spin of the Earth. New-fangled computers helped but were rare, so engineers had to queue up to use them. They had to figure out how to build navigation systems for space where there is no up, down, north and south, then they had to stop astronauts inadvertently messing with the systems. There were back-up plans for back-up plans and endless hours of testing for the dangers of freezing, burning and crushing. In his ‘Short History of the Space Race’, Reaching for the Moon, Roger Launius says the missions were a ‘triumph of management’. NASA not only had to build rockets and spacecraft through hundreds of sub-contractors, they also had to train astronauts, build launch pads and the means to transport the rockets there.

The whole world was watching… and cheering. Or so it is remembered and played up in hagiographies. But even Americans were lukewarm. After Sputnik, says Brown, Americans ‘nearly lost their minds’. But the hysteria faded. By the time of the Apollo missions, Americans tuned in to the drama but they also questioned the cost, and there were pressing concerns in their own country – the Vietnam War, Civil Rights. Rev. Ralph Abernathy of Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference organised a protest at the launch of the Apollo 11 mission that landed Neil Armstrong on the Moon. Though not against space travel per se, he lamented the colossal expenditure and lack of sensible priorities, pointing out that the Moon landing hardly benefited black Americans. Others were thankful for the celestial distraction in the year of the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy.

Against the naysayers, there were scientific gains – greater understanding of the formation of the Moon and planets, as well as weather systems back on Earth. It is arguable that the same results could have been obtained from robotic missions, but the point was simply putting Americans on the Moon first. Launius argues that the images of Earth from space and feelings of being all in it together also kicked off the environmental movement, but it was more likely the movement simply found the imagery suited the growing recognition of a fragile planet imperilled by fossil fuel consumption, international competition and blind faith in technology, of which the space race was symptomatic.

Both books point out how the space race developed out of the Cold War and was a de facto missile war, a way to let off steam, a very expensive kind of Olympic Games. Kennedy is remembered as a ‘visionary’, but he admitted he was not that interested in space, and only wanted to beat the Soviets at something, after the Soviets had achieved the first artificial satellite and the first man in space. Kennedy’s announcement of the Moon shot was only part of a longer speech about containing communism.

Launius and Brown put the Moon landing into the further context of the counter-cultural chaos of the late 1960s. Apollo, alternatively, showed white men doing heroic things, perhaps reassuring middle America that old hierarchies were still in place. The poet W H Auden was unimpressed at the time and wrote derisively that conquering barren, useless territory at great cost was a typically masculine thing to do. Interestingly, the Soviets sent a woman into space, but only as a publicity stunt, even though women actually performed better in space than men, and although the Americans trained women for the Moon, it was only in the 1980s that the first American woman made it to space.

Some said the Moon landing proved humans had the ability to do anything, including great acts of altruism. But once NASA made it to the Moon the public quickly lost interest. Maybe it simply proved our love of being on the winning side, as well as our capacity for being distracted by the sparkle of technology, rather than our ability to share what we have here on Earth.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com