A Painted Landscape, Amber Creswell Bell, Thames & Hudson.

Australia’s most famous artists are painters of the land rather than figures, cities or abstracts, such is the hold of the landscape on us, which even the irreligious describe as spiritual. Despite the fact that most Australians live in an urban environment, we have the sense of the wilderness at the edges of our cities and towns, which manifests itself in the common use of the word ‘bush’ (rather than ‘countryside’). Sometimes we talk as if we are guests at best, interlopers at worst, but to be Australian is to somehow grapple with our place in the landscape.

A couple of decades ago landscape painting was out of fashion, partly because of our cultural cringe-like desire to emulate the cosmopolitan, avant garde art of Europe and the US. There has been a resurgence lately, as indicated in this collection of contemporary landscape painters, not just despite, but because of, the increasing predominance of the urban. Not only is the bush a wild alternative, but it is also, as the appropriately named artist Holly Greenwood describes it, ‘replenishing’.

Of course this is not a simple either/or proposition. As A Painted Landscape shows, the urban is landscape too (in fact the word landscape originally meant land altered by humans). The urban has its own points of interest, as indicated by the art of Reg Mombassa, and John Bokor, who paints suburbia in bright, fauvist colours. Bokor says, rightly, that most Australians don’t live in the Outback. On the other hand, artists such as Clifford How are attracted to remote, ‘uninhabited’ areas precisely because they are so different to what is familiar to most Australians. Indigenous Australian artists in remote areas depict landscapes that may be unfamiliar to city-dwellers but are home and deeply connected to them.

Many of the artists in A Painted Landscape comment on the difficulty in responding to the bright Australian light, which one artist describes simply as ‘so intense’. John Olsen notes how long it took for European artists to adjust. Some artists, such as Ken Done, play up the intense colour. Mervyn Ruduntja (from the Hermannsburg watercolour tradition) and Neil Frazer focus on the reds and purples of rocks. Wendy McDonald’s paintings, alternatively, convey a pale, sun-bleached nature. (The inclusion in the book of photographs of landscapes depicted helps to identify what characteristics artists are pulling out and placing into their work.)

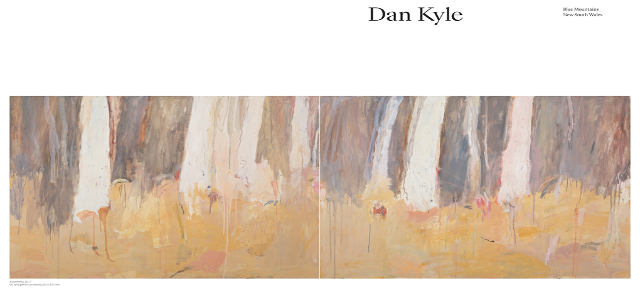

It is the nature of the book that the juxtaposition of artists highlights just how varied both subjects and styles are. One can turn from a page of Ken Done’s vibrant harbour scenes to misty, moody thunderclouds. Almost anything goes, from Nicholas Harding’s lively but meticulous dabs applied with a palette knife, to Jane Tangney’s meditative blocks of cool tones. The almost bonkers Natasha Bieniek paints micro-realist works inspired by sixteenth century miniaturists. She shows that the Australian landscape can also mean botanical gardens, and she revels in the intricacies of varying foliage. In contrast, Elizabeth Cummings highlights the apparent untidiness, energy and juxtaposition of colours in the bush by using an abstract style that she says conveys qualities not possible through conventional landscape painting.

Charmaine Pike, who reduces the landscape to blunt, outlined, ‘moody’ forms that reminded me of Philip Guston’s style, paints from memory, in the studio, and lets memory dictate what comes to the fore. Robert Malherbe, on the other hand, says he has to be outdoors for inspiration. Others do both. Working from photos and the immediacy of outdoor painting create different outcomes. But

many speak of the urgency to hurriedly get down a feeling when challenged by the shifting light or being overwhelmed by surroundings.

Abstract and realist is not always an either/or. Neil Frazer’s paintings of Outback gorges convey, according to the book’s compiler Amber Creswell Bell, ‘energy rather than actual intricacy’ but he is masterful at using the accidents of oil paint’s application to mimic the random busyness of a rocky landscape. Julian Meagher’s paintings of seaside vistas combine silky backgrounds with free swashes and dribbles, and the eye is pulled back and forwards between the evocation of the sea and the evidence of the physicality of painting such that his paintings become like optical illusions.

John Olsen says that an artist must focus purely on the quest for visual capture, minimising the political, but he also speaks of Australia’s interior as our ‘soul’ or ‘unconscious’. A number of artists comment on the fact that their art reminds them of Australia’s Indigenous history. Contrary to Olsen, the spiritual is not easily separated from the political. Life is not that easily compartmentalized. To recognize Indigenous history and connection to the land is to enter into contentious but unavoidable territory. If art connects us more deeply with the land, it also connects us to the uncomfortable fact that it is appropriated land.

Furthermore, landscape art reminds us of environmental political realities. To see the land properly is to understand the urgency of caring for it. The Australian landscape, says one artist, is ‘incredibly fragile’, underscored by the fact that the book concludes with Laura Jones’s paintings of the Barrier Reef. The role of art is not merely to make us look again for the sake of looking, but to help us understand the world and our place in it, and our responsibility for it.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com