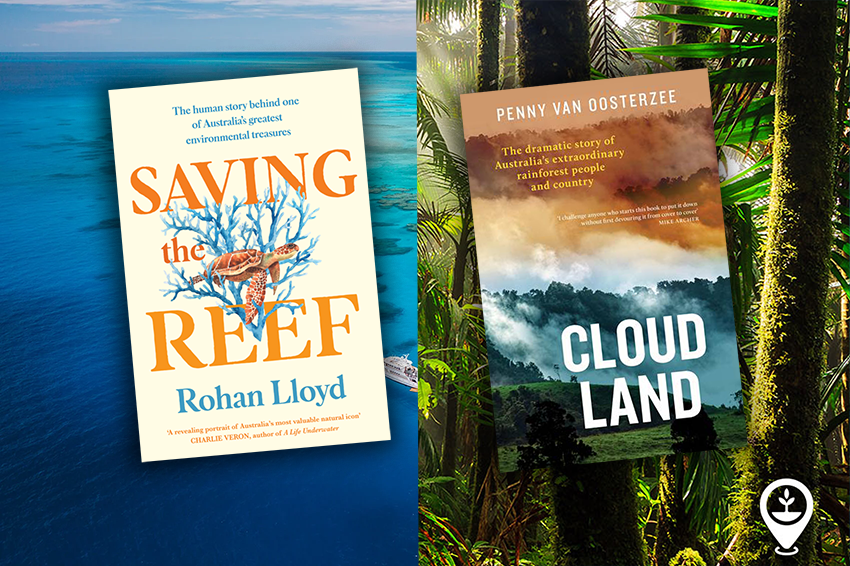

Reviews: Saving the Reef by Rohan Lloyd and Cloud Land by Penny van Oosterzee

The Daintree Rainforest and the Great Barrier Reef are national and global treasures, World Heritage Areas, tourism drawcards, long managed by Indigenous people. But settlers and colonial Queensland governments have been, until recently, keen to plunder them, and their continuity has only been a result of determined resistance by those attuned to their ecological significance, as these two books describe.

Early European settlers saw the Reef as both resource and beauty, says Rohan Lloyd, but size seemed an impediment to thinking that exploiting the former would affect the latter. Indigenous peoples were appalled at Captain Cook’s crew’s greedy harvest of turtles, but the crew probably thought the abundance was inexhaustible.

Seeing the Reef as resource and beauty simultaneously continued into the 1800s. Tourism was promoted, even if sometimes there were some odd attitudes – goats were introduced onto one island which was then extolled for its ‘exotic’ wildlife. But the Reef was also harvested for lime, pearls and dugong. In the early 1900s there were actually concerns it would be underutilised.

But already by 1922 the Cairns City Council was opposing lime mining on one cay because of birdlife. After WWII, resource talk spooked the public. After-all, in the 1950s the Queensland government wanted, to quote Trump, to ‘drill, baby, drill!’ The government legislated for oil exploration while at the same time said that they needed more money for tourism. Into the 1980s the government was still pushing for resource extraction licenses. Police intimidated scientists and protestors. It didn’t help that Premier Bjelke-Petersen was, says Lloyd, a significant shareholder of mining companies.

The Reef may be huge, but it is fragile, susceptible to climate change and other human-created threats (for which Queenslanders can’t be held wholly responsible). A Royal Commission and scientific studies showed the dangers, green bans from unions stopped exploration, voters turned against the Queensland government. But climate change-induced coral bleaching, acidification and starfish invasions are now part of a projected, previously unimaginable decline.

The Daintree may have been saved, but it is only a sliver of the ancient biodiverse rainforests that covered the Far North Queensland coast. In Penny van Oosterzee’s book, the first half is about the Daintree’s riches, the second about dispossession and despoilation.

Cook had noted, contradictorily, that Indigenous residents lacked for nothing, but the land was unproductive (he meant, one assumes, for European style farming). The settlers disagreed with the latter, setting out to destroy the forest to log cedar then sowing inappropriate crops, after not just pushing out but massacring whole villages that had welcomed them. (We now know this, but there continues to be a resistance to acknowledging it, perhaps because it doesn’t fit an image of Australia most Australians hold). Crops and dairies failed and because settlers didn’t understand the link between rainforest trees and soil stability, clearing caused erosion, polluting streams. (Agriculture run-off in turn damages the Reef.) Van Oosterzee likens all this to the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs.

This legacy is evident in the still-cleared hills of the Atherton Tablelands, where only fragments of pristine forest remain. The World Heritage Area, classed as the second-most ‘irreplaceable’ area on Earth because of its biodiversity and history, is only there because of the efforts of the Hawke Labor Government, against the protests of Bjelke-Petersen and John Howard.

Van Oosterzee owns land in the Tablelands, which she bought from a farmer determined to add to the destruction, and has set about reforesting it. It is now recognised that isolated pockets are not enough, as small populations decline genetically without wider interaction, so van Oosterzee’s contribution is part of wider endeavours to plant forest corridors in a web that links and strengthens remnant areas. This is especially important when climate change is causing movement of species. Unfortunately for some, time may be running out, for as the forests warm, species are pushed up the slopes in search of cooler areas, until they have nowhere else to go.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.