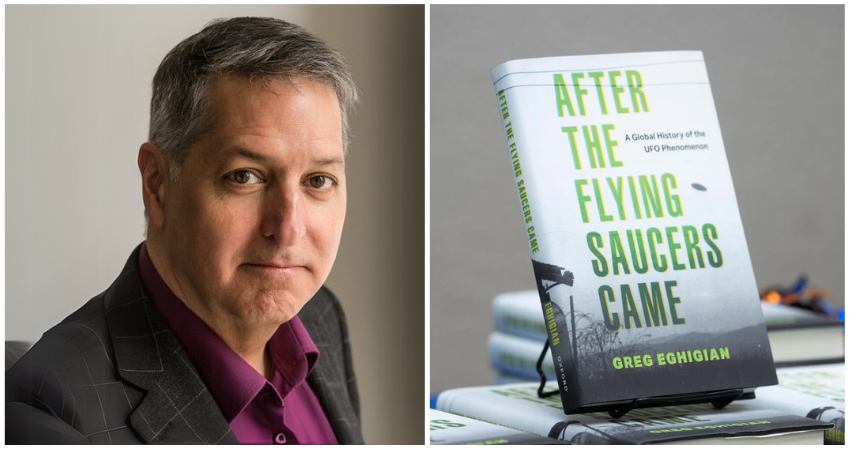

After the Flying Saucers Came: Greg Eghigian, Oxford University Press

Renewed interest in the UFO phenomenon lately is largely the result of the release of strange US defence videos and prominent whistleblowers coming out of the woodwork to testify to US government inquiries. But Greg Eghigian suggests that the history of UFO beliefs is less about conspiracies and more about psychological needs. At least one UFO researcher, during the heyday of UFO speculation, traced a trend of UFO sightings going up when news is bad and people are pessimistic about the future, suggesting an almost-religious element to UFO encounters. A Swedish UFO researcher described his work as a ‘spiritual quest’.

Eghigian’s book follows Garrett Graff’s recent book, which focussed largely on the US; Eghigian’s is a more global history; the ‘phenomenon’ is wider than reports from susceptible Americans. In the 1940s and ‘50s there were sightings of cigars, disks, balls and flashes of light in Argentina and Brazil, reported by policemen and pilots. There were sightings in Italy, Mexico and Russia. The French were especially keen to speculate on the origins of a rash of aerial phenomena there.

In 1947, US pilot Kenneth Arnold was responsible for inadvertently naming flying saucers: he described UFOs over Washington state as being like saucers (but also, contradictorily, ‘bat-shaped’). UFOs of course need not be extraterrestrial, and Arnold thought them likely to be of US Air Force origin. After-all, after World War II, and at the start of the Cold War, there was a fear of destruction from the skies, and people were more alert than they had been. Swedish reports in the late 1940s were put down to Soviets testing captured German technology, though this was never verified.

Weather balloons were a common go-to explanation, as were natural celestial bodies such as Venus. Some UFOs were simply classified as ‘unidentified’ – that’s all. Government officials and popular science writers alike, concerned about hysteria, set about debunking. At the same time there was a growing movement of believers.

By the 1950s there were magazines reporting on sightings, and budding ufologists clipped newspaper articles and shared them with pen-pals around the world. Clubs were started, lecturers toured. Global societies encouraged witnesses to write in. Members included both sci-fi fans and the more technically minded. They saw themselves as investigating where the government, for whatever reason, was reluctant to. (One magazine editor claimed to have had a discouraging visit from ‘men in black’, initialising an ongoing mythology.) Though many groups failed from lack of funding, there was the occasional success, such as CRIFO, set up in 1954 and called on by the US government to authenticate reports. Even Prince Philip was a subscriber.

Japan had, in the 1950s, the Cosmic Brotherhood Association, which forecast global catastrophes and rescue by aliens. A Malaysian journal reported on incidents across Asia, and Chinese groups, despite government scepticism, also published sightings, noting that the Gobi Desert was a favoured landing site. In the 1950s there was an amateur Australian Flying Saucer Bureau, and by 1965 a government investigative body.

Often ufologists were also interested in the occult, and sometimes the two phenomena came together. One group in the California desert had ‘contact’ sessions with aliens that were much like seances. Through the 1960s and ‘70s enthusiasts gathered annually, organised by someone described as a modern-day John the Baptist. A dark turn in this style of religiously motivated interest in aliens was the Heaven’s Gate cult, which mixed millenarianism and belief in ETs and led, in 1997, to a mass suicide, when members fatally poisoned themselves at the appearance of the Hale-Bopp comet, as preparation for union with aliens and an eternal post-human existence.

Early supposed contactees consistently claimed that aliens were concerned about nuclear weapons and offered messages of peace and hope, reflective perhaps of prominent concerns at the time. One popular author even claimed to have visited Saturn with benevolent aliens to participate in a galactic roundtable on the atomic problem. But there were also disturbing reports of abductions, which may or may not have had their own psychological explanations, and which had echoes of the demonic.

The most famous abductees were Betty and Barney Hill, who came home one night in 1961 dishevelled and with no recall of lost hours. (Being an interracial couple added to public interest in their story.) Undoubtedly some abduction claims were fuelled by lurid pulp fiction stories, and some were hoaxes, but Betty and Barney seemed genuinely disturbed by the experience.

The Hills underwent hypnosis to try to uncover the details of their abduction. To the couple’s annoyance, the hypnotist decided they had seen a UFO, but that Betty’s recall of being abducted was simply recall of a nightmare. Hypnosis featured prominently in the work of Budd Hopkins, who in the 1980s was convinced that hypnosis uncovered an ‘epidemic’ of terrifying abductions. But as with the so-called Satanic Panic of the 1980s, where hypnosis supposedly revealed episodes of child abuse that were later debunked, the hypnosis program was increasingly criticised as illegitimate. This, however, cannot immediately discount the mass of abduction stories coming from the likes of South America.

Eghigian is careful not to judge such reports but notes the regular combination of reported contact and a pre-existing interest in a wide range of paranormal subjects. (Of course, there are also those contactees who claim no prior interest in such things until contact.) Eghigian decides that interest in what UFOs actually are, whatever the truth of the matter, is in line with a long history of wider human interest in and experiences of phenomena that can’t be easily explained by mainstream science. This may be something less than conclusive, but it suggests that, whether they are here or not, aliens are not going away anytime soon.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.