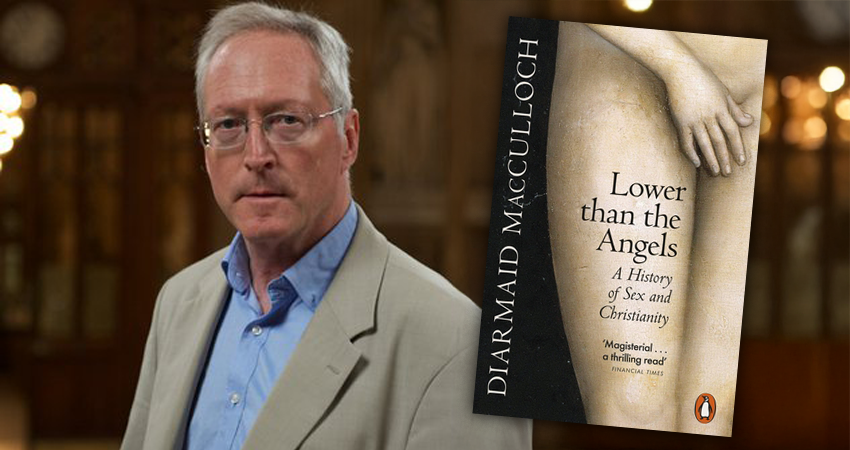

Review: Lower than the Angels: A History of Sex and Christianity, Diarmaid MacCulloch, Allen Lane/Penguin

In Christian bookshops there used to be – and I presume there still are – books celebrating sex within marriage, but in the history of Christianity this is something of an anomaly. For much of this history, there was a suspicion of sex, even within marriage, and celibacy and virginity were celebrated as next to godliness.

Diarmaid MacCulloch leaves no bedsheet unturned, though the reader looking for something racy in his new book will be disappointed. They will find, however, a typically long, nuanced and detailed discussion of sexuality, gender and much more besides. As in his other large books, MacCulloch is keen to show that this history is complex and that there have been various views and doctrines over the centuries – that, as with other issues, the Church’s views on sexuality have been a long ‘dialogue between theology and circumstance’.

Sexuality and gender seem, at times, to have loomed disproportionately large in Church history. As James Boswell once said obliquely of the issue, no-one was ever burned at the stake for greed. But MacCulloch cautions against assuming that terms we use today mean today what they meant in the past, and he notes that when it comes to sexuality the Church’s focus has been different at different times, just like, say, the finer points of Trinitarian theology, which were a life-and-death issue at one point in Church history but attract little controversy today.

In the Gospels, Jesus is strict on divorce, invoking traditional Scripture, but unorthodox in his approach to adultery, recognising that sexual ethics is inseparable from questions of cultural power. While Judaism celebrated family and children, Jesus was famously dismissive of family, which should make conservatives think twice about ‘family values’.

Saint Paul, too, was unenthusiastic about marriage, but this could be because the early church thought of itself in an end-times position. This context is often forgotten, says MacCulloch, when universal doctrines are extracted from Biblical exhortations. This goes for the modern issue of women in ordained ministry. Incidentally, MacCulloch notes that the debates around female leadership in the epistles indicate that there must have been many female leaders; after-all, he says, you don’t need to constantly debate banning things that are exceedingly rare. There seems to have been various currents here – although some epistles reinforce gender hierarchies, it seems the early church was also upsetting them, MacCulloch says.

Paul, MacCulloch writes, is inescapably responsible for suspicions around sex, and this led to the celebration of celibacy and the rise of monasticism. But, as there would be for centuries after, there was also some concession to the society around the early church, as, when Jesus didn’t return immediately, the early church had to survive and recruit. And so, over the history of the Church, we see it both influencing and being influenced by the laity. And, although it doesn’t always come out in this book, throughout history there has been a difference between what the Church said and what the laity did.

Within the early church we see an emphasis on spirit over body (reflective perhaps of Greek over Judaic influence), and it is sobering to recognise that this would lead to, within the monastic tradition which would come to dominate the Western Church, celibacy being seen as the default position for heightened spirituality. There was some logic in this development, as Jesus had said that his followers would leave their families and follow him. A focus on asceticism, which begins early in the Church, would almost naturally run to the avoidance of sex. In the fourth century, Jovinian, a monk, was regarded as a heretic for sticking up for marriage.

It’s not just that celibacy was celebrated; sex was denigrated. As usual, the issue is complicated, but Saint Augustine can be held partly responsible for the long historical view of sex as sin, even within marriage, and this would lead to abstinence before receiving the eucharist and the doctrine of the immaculate conception. During Augustine’s time there was already talk of Mary’s supposed perpetual virginity. Virginity within marriage was celebrated as preparing one for sainthood. But one had to be careful: to say that physical things were bad steered near the heresy of Manicheism, the medieval version of which was Catharism, whose devotees dismissed all physical things as bad, including the institutional church (and were therefore hunted ferociously). We might add that this fear of sexuality also went against the notion of the Incarnation, which emphasised the godly manifest in a real human body, with all that that entails.

Despite monastic celibacy, it would be only in the eleventh century that celibacy would be extended to priests in the Gregorian reforms, which were complicated by the issues of inheritance of church property and priestly dynasties. Celibacy would be enforced to varying degrees by church authorities who, in some cases, told married priests simply to hide their children and not flaunt their partners in public. The enthusiasm for celibate priests was not just top-down – the laity rioted and broke into priests’ houses to remove their wives, though this was not widespread, and before the Reformation there was never a completely celibate clergy.

The Reformation was probably reacting as much to hypocrisy and unrealistic expectations as it was to priestly celibacy per se, but as monumental as salvation by grace was, the destruction of monasticism and ridding the clergy of celibacy was a driving force. MacCulloch notes that rejecting priestly celibacy was one of the few things that united Protestants.

One result was that priests who hadn’t quite been celibate married their concubines. Some nuns undoubtedly married because they wanted to; others may have been forced into it in the suddenly tumultuous climate. Luther (or the local pastor) and his family suddenly became the exemplars for lay families. This was a seismic shift. While the pulpit had renewed centrality in Protestant Christianity, so did the kitchen table. In both Protestant life and in the Catholic Counter-Reformation there was a new emphasis on the Holy Family.

The Reformation and Renaissance, then Enlightenment, may have seemed more enlightened times for women, though MacCulloch, otherwise focussed more on church authorities and men, suggests that while there were many fine words, in everyday life, ‘far less may have changed’ for women. In the twelfth century, theologian Peter Abelard had championed the ordination of women, as well as arguing that something as pleasurable as sex couldn’t be sin, but he was castrated for his troubles. John Wesley promoted female preachers, but Methodists curtailed much of that after this death. It is only in the twentieth century that women would see more freedom (and more confusion for conservatives).

There were varying views on homosexuality too, and throughout the Church’s history focus on it waxed and waned. By the sixth century the Church, with more authority, was cracking down on same-sex acts after not focussing on them much earlier. In the thirteenth century a bizarre extra-biblical story developed that at the birth of Christ all ‘sodomites’ had died. Yet the Middle Ages, through classical influences, saw some literary celebration of same-sex couples. And there were extraordinarily rich and prominent declarations of love between monks, even if at least some of them remained celibate.

In the twentieth century there was, for the West anyway, an extraordinary divergence of Church and Western society. Christianity was, and remains, the world’s largest religion, and churches would initially be united over the post-war (so-called) sexual revolution, which coincided with the waning of church influence in the private sphere and the availability of contraception. This unity wouldn’t last long, and over sexual matters, MacCulloch suggests, the Church has never been more divided.

The twentieth century saw a reassessment of the subordinate role of women, and the churches were not always behind here. The Church of England was ahead of the nation in giving the vote to women. But in other matters, a series of clerical scandals, within all denominations, laid bare hypocrisies and the unrealities of clerical celibacy.

In Evangelical American circles, the sexual revolution was combatted through a shrill insistence on the family – meaning nuclear heterosexual family – where sex is seen as a blessing, but strictly within marriage, even if many Protestants embraced the new availability of contraception. In the wider culture, the idea that Christians are prudish about sex persists, along with the idea that Christians are less likely to support gender equality. MacCulloch says modern conservative religious men are angry at their loss of power, but it is more than this: the messiness of modern gender identity and sexuality challenges simplistic but reassuring doctrines. Now, stances on trans identities and more have been added to abortion as signs of political affiliation.

MacCulloch is of the opinion that those in a hurry to make public pronouncements on sexuality, especially from a conservative stance, simply don’t understand the historical context. His hope, partly with his own experience within the Church in mind, is that a better understanding of changes in attitudes within the Church over history will lead to at least more openness and humility today.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.