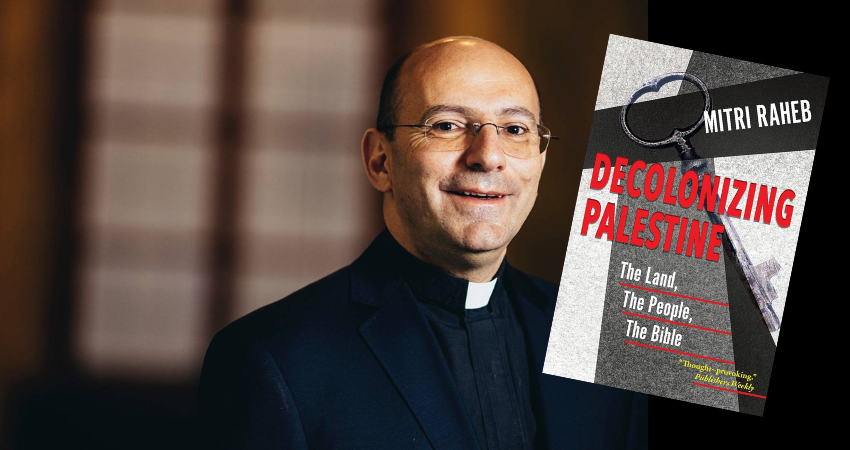

Review: Decolonizing Palestine: The Land, The People, The Bible by Mitri Raheb

It could not be more timely to review Mitri Raheb’s Decolonizing Palestine. The situation in Gaza cannot be separated from what is happening to settlements on the West Bank. Raheb’s particular focus is on the Zionist practice of a settler colonialism that effectively displaces an indigenous people. It is not the same as an ‘occupation’. It is manifested through ‘the permanent settlement of colonists in an occupied land’ and the capacity to ‘enforce state sovereignty’ and ‘juridical control’ (p. 3). The accompanying political and hermeneutical rhetoric is inclined to make the ideological cases where these new settlers are the rightful inhabitants of the land: ‘a land for the landless’.

For western Christians Raheb’s practice of decolonisation is uncomfortable. It is so on several grounds. The analogy is made between this expression of settler colonialism and what unfolded in the United States, South Africa and Australia as a consequence of the geopolitics of empire. Raheb is insistent in this argument. The current situation in Palestine is set within the support extended to European Jews with little awareness of those inhabiting the land. Raheb demonstrates how the beliefs and practices embracing Christian Zionism can be found in liberal as well as more conservative evangelical theologies and their turn to Old Testament prophets and End Times scenarios. The very nature of a salvation history appears to allow biblical promises to do with the land to be equated with the modern state of Israel. The ideological construction that dispossesses the Palestinians is further reified through the continuing legacy of post-Holocaust guilt. Might the evident success of the 1967 war justify the acquisition of new and unlawful territories? Might that not be seen as a sign of God’s protective faithfulness?

The hermeneutical and theological task before Raheb is daunting: the soft reading of the dilemma is partly one of how ‘Christian Pilgrims visit Palestine [and] only want to reinvent the holy land of the Bible’ (p. 53). The more serious and disturbing reading is the way in which the ‘ancestry’ of the land, Palestine, has been interpreted in ways that can justify conquest and settler colonialism. The biblical story is used as history. Raheb calls into question the practice of identifying Abraham and David with the modern state of Israel. He is well aware of how important names are in framing understanding – ‘for naming is an exercise of power’ (p. 57): for that reason, he provides a most helpful account of when and to what the terms Canaan, Palestine, and Israel were applied. Raheb provides biblical examples of Israeli politicians justifying settlement and which can lead to indigenous Palestinians being seen as ‘aliens’ and ‘strangers’ in their own land. The book of Joshua, in particular, has been co-opted into this ‘tunnel vision’ (p. 63). The tendency to weave together land, God, and Israel (the state) can happen—sometimes unconsciously, sometimes not—in more liberal forms of Christian biblical scholarship. Raheb maps the evolution of Walter Brueggemann’s scholarship in this respect (pp. 67-73): it is time for ‘theological innocence’ to end. The stakes are high: ‘Land theology has been a theological tool for Palestinian dispossession and oppression’ (p. 80). The state of Israel is one of exclusion and a trend towards a contemporary equivalent of apartheid. The comparison can be made with the prior experience of Palestine, where different cultures and religions effectively lived side by side within a ‘dynamic flexibility’ (p. 83). Raheb situates the consequences of this ‘distortion of history’ and ‘poor biblical interpretation’ within a geopolitical worldview of post-Holocaust guilt and the politics of Western empires. Now he argues the case of a decolonial hermeneutic of the land: he privileges the intervention of Elijah on behalf of the exploited and killed Naboth (1 Kings 21) and a reading of Matthew 5:5 in the light of Psalm 37: ‘Blessed are the meek for they shall inherit the land (rather than the earth)’.

Raheb’s pervasive concern for history, interpretation and naming becomes even more focused in the discussion surrounding the election and the identity of the chosen people. (Raheb distinguishes four different usages of the word Israel (pp. 93-94). The risk for contemporary Palestinians lies in the manner in which the Hebrew Bible is interpreted as the history of the Jews as people and when the notion of election is weaponised politically to give modern Israelis a carte blanche for their discriminatory policies (p. 96). It is ‘weaponised’. From what is a subaltern position, the ‘hardware’ of military occupation of Palestine comes with ‘software’ readings of biblical concepts to do with election, land, and chosen people (p.97). Palestinians tended to be ‘equated’ with being Philistines or ‘cursed Canaanites’ (p. 97). As Arabs, they become the descendants of Ishmael. Of critical importance to his decolonial understanding of election are distinctions he makes between story and history, between particularity and singularity. Raheb practices a reading based on the prophetic resistance to empire, ancient and modern. The Bible is a story that requires interpretation; the particularity of the storyline cannot be reduced in a context facing an empire in such a way that the election of a people is singular, only meant for one group. It is a time for prophets to issue their warnings. Raheb argues that an election cannot be understood in a linear history of salvation that ignores the geopolitical context of the originating past, let alone that of the present.

Raheb’s decolonising thesis situates the suffering of Palestinians within the geopolitics of empire. It presumes a reading of the Bible from the geopolitical perspective of the time in which Biblical texts were set: it invests in a hermeneutic of suspicion with respect to their current reception. This framing is both understandable and necessary given the way in which the Bible and theologies of election and land have been deployed to justify settler colonialism and garner international support. Now and then, the tendency to invoke a homogenised politics and perspectives of western empires and settler societies is insufficiently nuanced – but not in such a way that it invalidates the powerful case Raheb makes.

Assoc. Prof. Clive Pearson is a Session Lecturer at United Theological College

Picture credit: mitriraheb.org