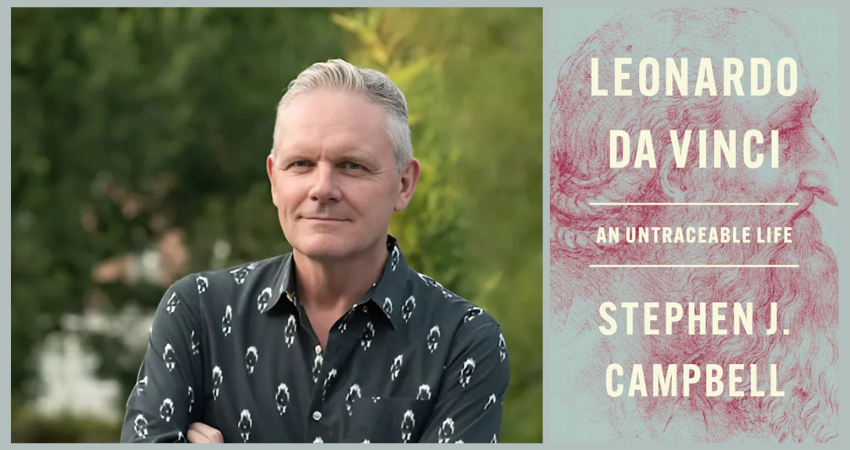

Leonardo da Vinci: An Untraceable Life, Stephen J. Campbell, Princeton University Press

It’s a rather strange way to begin a biography, and it seems like an undersell, to emphasise how much we don’t know about the subject in question, but Stephen Campbell’s argument in this book is that we don’t know Leonardo da Vinci well, and what we think we know is often legend and speculation. Biographies of Leonardo, of which there are many, suffer, according to Campbell, from an unusual degree of confidence, despite the lack of sources and the confusing nature of those that exist.

This is not a popular biography like Walter Isaacson’s. Rather, it reminded me of Miles Hollingworth’s amazing biography of Ludwig Wittgenstein – passionate and unorthodox and as analytical of the art of biography as much as of the subject himself. Campbell describes it as an ‘anti-biography’ in which he constantly questions the assumptions that turn up in other biographies and is critical of biographers who extrapolate from the tiniest of clues that might not be clues to fit a preexisting conception of Leonardo as the prototypical modern man.

There is a great desire to know the man, in order to illuminate the works, and vice versa. But unlike Michelangelo, who was forthright in his writings, Leonardo is distant, even in the hundreds of pages of notes he made, which Campbell finds contradictory and messy. Campbell makes a distinction between the more obscure ‘Leonardo’ and the ‘Da Vinci’ of popular imagination that propels exhibitions, books and merchandise – what Campbell calls ‘Da Vinci World’.

The first assumption about ‘Da Vinci’ is that he was a man of science – ‘ahead of his time’. His inventions and studies of optics seem to fit this image of the scientific, though the term ‘scientist’ would not be commonly used until centuries after Leonardo. Newton is a comparable figure – he seems like the epitome of scientific rigour, but Newton spent as much time thinking about alchemy and eschatology as he did gravity.

Leonardo did make dissections and detailed anatomical drawings, but contemporaries were exasperated by his chaotic working methods, his inability to finish things and his propensity to jump from one project to another. And in his writings Leonardo criticised the utilitarian (‘scientific’ in later parlance) attitude of ‘just the facts’. He understood that reductionism was necessarily a diminishment.

Campbell emphasises that we don’t know Leonardo’s exact beliefs, but paintings like his Last Supper indicate deep biblical knowledge. Modern interpretation has it that Leonardo was only interested in the psychological drama, and that the evidence for this is that there are no halos in the picture. (Campbell says there probably were, but they have been lost over time.) But the painting shows an understanding of both the human drama and the sacramental importance. In his other paintings, the link between observation and depiction is often emphasised, but Campbell stresses that Leonardo’s paintings are loaded with symbolism, mostly of a religious kind.

Furthermore, Campbell suggests that when we look for evidence of Leonardo’s spiritual self, we are looking with modern eyes and fitting the evidence, or lack of it, to a modern conception of the self. In contrast, in the Middle Ages, religion was more about action and belonging to a community than holding individual beliefs. Leonardo stated that he left spiritual speculation to friars, but that is not evidence of a lack of religiosity. In his writings, he may have disparaged miracles, but he also made reverential comments about God.

Campbell writes that using documentary evidence to construct a modern biography of Leonardo is somewhat anachronistic, as the sense of self in Leonardo’s time is very different to ours – in particular, we stress the autonomy of the self, but in the Middle Ages, as in Indigenous cultures, the self is defined by where we sit in a web of family and friends. Leonardo’s art can be better understood by investigating his social circles and influences. Campbell adds that putting Leonardo in a box of contemporary identity politics is the wrong way to go about it.

It suits the modern perception of the self to see Leonardo as a loner – this fits our conception of solitary genius. I think this is similar to Galileo, who is pictured as the rebellious genius sticking up for science in the face of aggressive superstition, a picture that is regrettably simplistic.

There is a modern obsession with attribution, none more so than over the Salvator Mundi painting, now hidden somewhere in the Middle East. But we don’t know enough about workshops in Leonardo’s time to know exactly when Leonardo was involved with particular paintings and when apprentices did the work. In Leonardo’s time, modern issues of attribution were not important – rather, the conveying of that workshop’s style was important. In this, Campbell returns to his running theme – that medieval ideas of self were very different to ours.

We don’t even know what Leonardo looked like. Supposed self-portraits (such as the one used on the cover of this book) may not be so, if the chronology is interrogated. But the speculation in the art world that is quickly elevated to fact is accelerated by the astronomical prices that Leonardo’s works fetch.

Despite the value of the paintings, we don’t know much about the methods. New technologies that allow experts to look under layers of paint help, but Campbell is sceptical of some of the conclusions, driven by the pressures of the commercial art world, including the desire for blockbuster exhibitions that supposedly allow us to see ‘behind’ the artworks (in both a literal and metaphoric sense) to find the ‘real’ Da Vinci. Instead, Campbell invites his readers to admire Leonardo’s art without assuming we have a historically unique insight into his personality.

The reality of the fragmented and shadowy Leonardo is perhaps exemplified by The Last Supper. Extremely fragile because of Leonardo’s botched technique, the painting was almost gone by the 1700s, when there were a series of ‘restorations’ guided by contemporary copies of the fresco. More modern restorations are, says Campbell, particularly in the latest bright colouration, a ‘postmodern simulation’. The current version is likely too ‘impressionistic’. From copies, we can see that it was probably bolder, but then, we just don’t know.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.