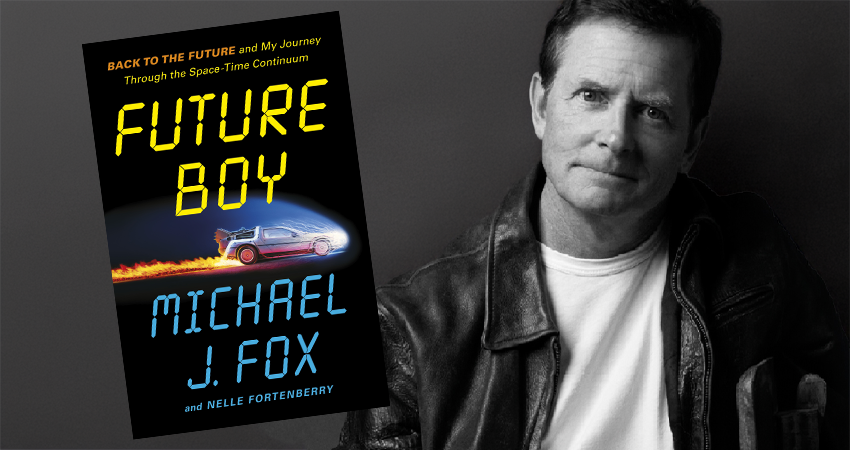

Review: Future Boy, Michael J Fox (and Nelle Fortenberry), Headline

This year sees the fortieth anniversary of the making and release of Back to the Future. Michael J Fox’s book comes piggybacking on the anniversary, and centres on the fact that during the filming Fox was inhabiting parallel universes – making a TV sitcom during the day, and sci-fi movie making at night.

It’s not a long book – stocking filler, basically. And although the publisher’s blurb suggests the story has ‘never been told’, that’s not quite true – the details of the half year of filming are all over the internet, in interviews with cast members and the like. Still, there are revelations here, Fox seems like a genuinely nice and humble guy (managing to both state and not overstate his achievements), even if he likes to play up the fact that he was something of a teen delinquent, and fans will appreciate the chance to again travel back to fondly remembered 1985.

Fox, the star of a hit TV show in 1985, was originally intended for the film’s main role, something he says he was surprised about, but unbeknownst to Fox, the producer of Family Ties had shut that idea down because of Fox’s commitment to the show, which was especially pressing because his on-screen mother was pregnant in real life.

But Eric Stoltz, the original Marty, had been too serious for the role, and the producers felt it wasn’t working out. (It is said that Stoltz himself didn’t understand why he was cast, even if he was disappointed to be fired.) After five weeks of filming, they again asked for Fox. This time, the Family Ties producer relented, as long as Fox would shoot the film at night, so as not to interrupt the Family Ties shooting schedule.

Fox jumped at the opportunity to work on a Spielberg film, even if it meant not having much time to sleep. This now-legendary, crazy situation, which went on for three months, wouldn’t happen today, it is said, with agents and lawyers, and more rules and control. Fox describes it as ironic, for a film about time, that they were so pressed for time. Einstein once said that time exists so that everything doesn’t happen at once; Fox says, for him, it felt like everything was happening at once.

The crew had to reshoot five weeks’ worth of material. (They tried to salvage some earlier footage, but this mostly didn’t work, due to the cooperative nature of acting, as Fox explains.) Fox was thrown straight into the nighttime carpark scenes where the Delorean time machine is revealed, without rehearsals. If Fox says he was a little bewildered at first, it was obvious to everyone on the set that Fox added the comic spark that was missing. Not only did he bring slapstick to the role, but he reveals he provided some of the best lines in the movie, deliberately or accidentally. Family Ties meant his head, as well as his body, was in the right comedic space.

Fox brought out the lighter side of the absurd premise of the film. Stoltz had, apparently, channelled the darker, tragic side of it – perhaps epitomised by the dark outfit he wore during filming, a look that would be reassessed with Fox’s reinterpretation of Marty and his iconic orange-red vest.

The producers had found their Marty, possibly because Marty was the closest of any of Fox’s characters to Fox himself – thrown into surreal situations, landing on his feet (after some comedic tumbles), and a lover of music. For Fox, the celebrated dance hall scene where Marty ‘invents’ rock’n’roll by playing ‘Johnny B Goode’ with Chuck Berry’s cousin (thereby giving more fodder for the comedy in the time travel paradox) was the highlight of his career, and he lovingly describes both the scene and its long aftermath.

The ‘Johhny B Goode’ scene was almost dropped by the producers – they didn’t see it as necessary to the plot – but test audiences loved it. There were other elements that the producers originally had in the script – the time machine as a modified fridge, an atomic bomb powering Marty’s return to 1985, George McFly implausibly becoming a boxer, the inclusion of a chimpanzee, and 1985 looking, on Marty’s return, like those visions of the future dreamed up by artists in the ‘50s. These were all sensibly scrapped, but, along with the inclusion of Eric Stoltz, there was the possibility of a different path on the space-time continuum and ending up with a much less satisfying, and probably unsuccessful, film.

Time travel films, the writers understood, hadn’t done well up to this point, but the honing of the script, the recasting of Marty and the fact that Marty accidentally, rather than deliberately, goes back in time, and messes with his family’s history, gave the writers a winning formula, what became in essence both a screwball comedy and a hero quest: Marty is Odysseus trying to find his way back home.

The germ of the film was a thought experiment from one of the writers, the ageless philosophical question: if I travelled back in time to go to my father’s high school, would we be friends? This turned into a version of the Oedipal paradox of time travel: if I travel back in time to kill my father, would I exist? In the case of Back to the Future, this became: if I travel back in time and stop my parents falling in love, would I exist?

In the end (spoiler alert!) things work out: not only does Marty return home, but he also has altered the course of history such that his father is now a successful author and the family well-off. One of the interesting aspects of the film’s history is the perspective of Crispin Glover, who plays George McFly. He is sometimes cast as the cast’s villain: a talented actor with a contrarian streak. He was unhappy with the materialist ending of the film – happiness is equated with financial success, symbolised by Marty’s new car (truck). (Glover’s objections were ignored.)

A related observation, interestingly, has been made about Fox’s Alex Keaton character in Family Ties. Alex was meant to represent how the ideals of baby boomer parents had been lost in their children, but Fox’s portrayal of Alex put a cherubic face on 1980s Republican materialism, softening the intergenerational contrast. Back to the Future’s ending seemed in line with the very 1980s and very American ideal of materialist individualism (not to mention righting wrongs through the use of violence), in contrast, it might be noted, to a film like It’s a Wonderful Life.

Yet this is complicated by the fact that Marty is glad to return to 1985 before he finds out about his family’s improved fortunes, and even if 1955 Hill Valley is portrayed as more idyllic than its 80s iteration. Home is what we’re used to.

It could be argued that material success is merely a byproduct of Marty’s existential objective of getting his parents together through empowering George. The ending of the film represents the ideal that Marty instils in his father (as well as in the town’s aspiring mayor): believe in yourself and you can achieve anything – something beyond simply a focus on material success. But then we might want to ask if that noble, but perhaps still very American, ideal is as universally applicable as the movies might make out, considering that in real life things are more complicated than movie endings.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.