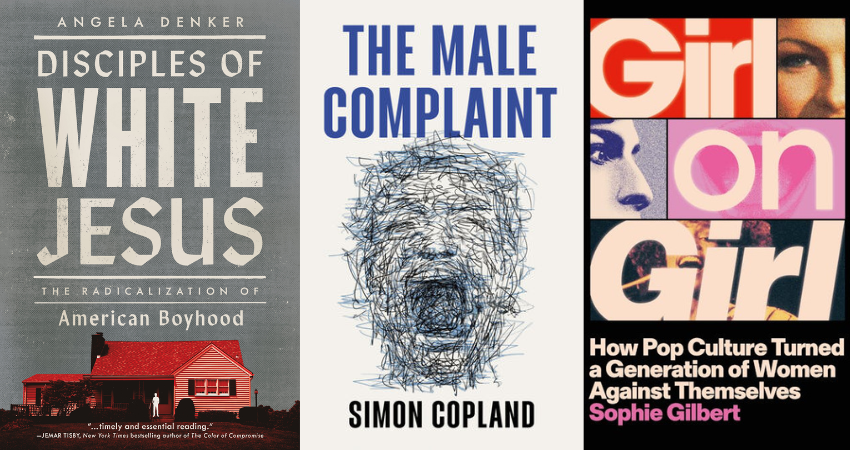

A comparative review of three timely works :The Male Complaint by Simon Copland, Girl on Girl by Sophie Gilbert and Disciples of White Jesus by Angela Denker.

These three books all, in their various ways, deal with a recent resurgence in Western culture of misogyny. They are not exactly fun reading but highlight an important issue that is part of a wider rightwards turn towards aggressive tribalism and push-back against what is derided as ‘woke’ culture.

Simon Copland investigates the online world of the so-called Manosphere – not so much the celebrities such as Jordan Peterson who contribute to it, but the regular guys who get online to share and cultivate grievances. Often this is labelled as ‘toxic masculinity’, but one of the strengths of Copland’s book is that he finds that label unhelpful – it suggests masculinity has an inescapable dark side – and instead makes the effort to understand why some men feel aggrieved (and mistakenly blame feminism). He writes that, of course, there is some lamentable behaviour that must be called out, but simple dismissal is unhelpful.

The answer, he says, is complex, but there are two, linked causes: a societal shift from contributing to consuming, entailing a loss of meaning, and an epidemic of loneliness that leads men to attempt to find community online. To say that men have overwhelmingly lost out recently is wrong, especially if we look at the likes of gender disparities in income and leadership roles, but those who saw masculinity in certain traditional ways are now challenged, and the loss of certainty, from work to family roles, is reflected in online conversations, just as it is reflected in politics, where both masculinity and femininity are talked about in narrow terms.

As part of a consumerist society, men are encouraged to think of relationships in consumerist terms. (In our society, Copland suggests, everything is commodified.) Sex becomes not part of a deeper relationship, but another want, and it is no surprise that much of the online discussions in the Manosphere are grievances related to being denied sex. This leads to a strange scenario where love is seen as a battle. Underlying this is a view of relationships as survival-of-the-fittest and essentialist, simplistic views of gender.

Copland argues, perhaps unsurprisingly, that to oppose misogyny and its associated violence we need to target the root causes rather than just trying to ban groups from social media and calling chauvinist men names. Understanding why Manosphere ‘leaders’ gain traction is important, and schools, sports clubs, homes and churches all have roles to play in getting in early and offering community for men susceptible to alienation. These men don’t need more ostracising.

Sophie Gilbert looks at similar issues, but from women’s perspectives, asking why, in the 2000s in particular, society went backwards in terms of positive views of women and their potential, when, according to her, 90s ideas of female empowerment changed to vacuous ‘girl power’, when, in popular culture, being a perpetual teen was seen as an ideal, personified by the Spice Girls, (actual teen) Britney Spears and TV character Carrie Bradshaw. Of late, while we have seen more positive messages about bodies, and the outing of sexual predators, there has also been a backlash in terms of the objectification of women and the fantasies (and realities) of dominant men.

In part, Gilbert blames the pervasive influence of pornography, in fashion, music and film, where it is filtered but traceable in how men think women should look and act and then how women think they should represent themselves. She sees this in hip hop misogyny – defended in the 2000s as ‘art’ but where some of the protagonists have been since charged with all manner of misconduct – and in reality shows like Big Brother, which suggested that the private lives of women should be on show. Like Collette Shade in her recent book about the 2000s, Gilbert also makes links between warmongering, military abuses and society’s attitudes to women, and, like Copland, she writes about the perils of consumerism and how advertisers, including female celebrities, cultivate dissatisfaction within women to sell stuff.

Gilbert must have a strong constitution, considering all the terrible films she watched as part of her research, both bad American comedies and violent pornography. In fact, there are parts of her book that might better be left unread. But her book rests on a fairly simple proposition that we often under-play: pop culture influences how we act in real life – and when women are portrayed well, they are treated better by men (and other women) in real life.

In her book, Angela Denker, a pastor and former sportswriter who has previously written about the mysteries of Trump voters, travels the United States to, as with many others, try and understand how what should be opposites – Christianity and prejudiced, aggressive attitudes – come together in the minds of some young white men and boys.

She investigates military culture at an academy, travels to the site of a massacre at a Black church, and to rural Minnesota, where she finds less tolerance for white supremacy, but a kind of default support for Republicans.

As a pastor herself she tries to understand the promotion of division and rigidity amongst influential conservative pastors, Mark Driscoll being one of the most prominent. More of a self-promoter than promoter of Jesus, Driscoll is now somewhat disgraced. But his influence still lingers, argues Denker, and his approach is not atypical.

Driscoll, a so-called new Calvinist, was one of the megachurch pastors preaching subservient wives. In this telling, marriage is a power struggle where, one assumes, males only grow in power as women lose power – a typically American focus on competition (although Tim Winton also speaks in an Australian setting of the danger of teaching boys that life is a fight). In light of this, it is not surprising that Driscoll argues for a macho image of Jesus – that Jesus was tough and responsible.

Denker notes that this then extends to a reading of Genesis that prioritises hierarchy (euphemised as ‘complementarity’) instead of contemplation of the picture of beauty and harmony that Genesis also conveys. All this leads to a kind of Christian ‘warrior’ culture where men feel entitled (mirroring and intertwining with the Manosphere), this in turn leading to anger when their expectations come up against the complexity of the real world.

She writes about the idea that ‘Jesus fought for freedom’ and how this spiritual notion is easily redirected to the political. With this mindset, she argues, it’s not much of a leap to align Jesus with Trump, and to reinforce divisions on racial lines. It is no surprise that misogynist views align with racist ones. (Neither is it then much of a leap to prolific gun ownership, sadly endorsed by many American Christian leaders.)

In this context we find, insanely, clergy being harassed by their own parishioners if they criticise ‘the President’ or show sympathy for Black victims of violence (which is, somehow, ‘Marxist’). While, from the outside, this looks insane, in the current climate, and under Trump’s ‘leadership’, it is easier to air such divisive and inflammatory attitudes.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.