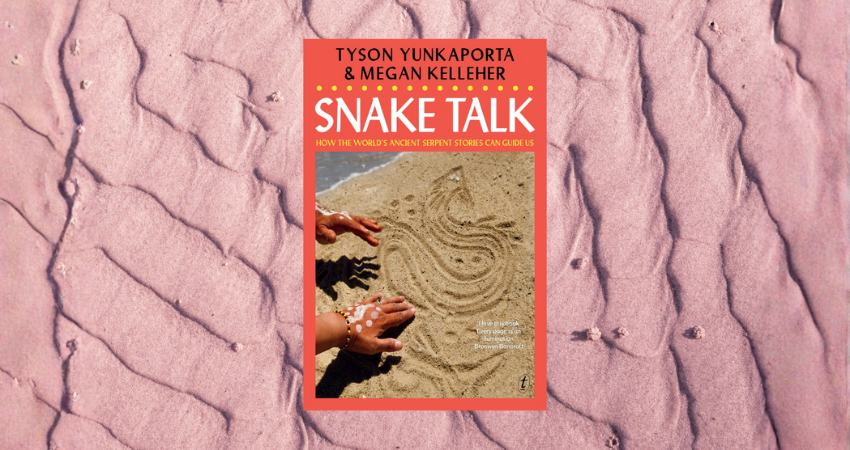

Review: Snake Talk, Tyson Yunkaporta and Megan Kelleher, Text Publishing

In the Jewish-Christian scriptures the snake gets a bad rap. In other spiritual traditions, the snake is more celebrated, the Rainbow Serpent being one example. Tyson Yunkaporta’s latest book, written with his wife Megan Kelleher, is something of an attempt at reptilian reputation rehabilitation, but also an attempt to take some wisdom for our ecologically shaky times from global snake mythologies.

Yunkaporta’s distinctive style is a mix of grand claims and an earthy, almost crude sensibility, with sarcasm and sometimes aggressive humour, verbosity and a cutting polymathic intelligence. His books have much wisdom, but I have also found at times that their effect can be off-putting for non-Indigenous people: he often indicates that while there is wisdom to be had, that wisdom is difficult for non-Indigenous people to access.

This may be the point. He criticises ‘New Age-y’ uses of Indigenous knowledge and its incorporation into corporate business philosophies (God help us). He repeatedly indicates, often humorously, that Indigenous perspectives can’t be cherry-picked or superficially laid over Western perspectives. They are not simply a tool but are inseparable from relationships that are underpinned by connections to land and tradition but are also open to dialogue and innovation.

There is also a view of the material and spiritual that is different from modern Western ones. It’s sometimes hard to know whether Yunkaporta takes literally talk of spirits in rocks and the like, but this may be the wrong way to look at it. The authors here write repeatedly about ritual, and how whether taken to be ‘literal or metaphorical’, ritual is a narrative that maps onto ecology. Ritual narrative provides ‘purpose’. It sets up and powers what we might call the ‘practical’. In the authors’ description of it, it is obvious that ritual, when done correctly, is energising.

Additionally, ritual narratives are corrective to individualism, situating individuals in a bigger story. Values get distorted by one individual – we need various ‘eyes’ to centre a vision, as they say

In this expansive spirit, simplifications are difficult. A summary won’t do justice to the meandering nature of the narrative, which makes its effect through slow seepage rather than injection. Still, at the end of the book the authors offer a page of short pieces of advice, and rather than repeating those, I might offer my own interpretations of their advice: be patient with stories, be comfortable with layers, respect different perspectives, don’t force your own views on others, the world is always larger and more complex than you think.

We might make other generalisations about what they take from snake mythologies. The Quetzalcoatl tradition of Central America suggests that difference should be seen as complementary rather than antagonistic. In snake mythology, women are often portrayed in a kinder light than the Garden of Eden story. Change is constant, and there are good and bad forms of change – the good ones encourage renewal and inclusion. Current Western predicaments are occurring because we are blinkered and think things can continue as they are. Indigenous thinking, rather, offers ways of adapting to change. Indeed, one of Yunkaporta’s repeated points is that Indigenous tradition is not unchanging. It is, rather, adaptable and evolving. (And it has to be: he is realist enough to acknowledge that colonisation is not being reversed any time soon.)

Yunkaporta’s style dominates the narrative, but in the context of the above, I was keen to hear more of Kelleher’s perspective. They indicate in the introduction to the book that he is atheist and she is Christian. (That’s how I read the inference.) He is scathing on Western Christianity; at his most generous he says that the stories are good but the doctrines aren’t. Considering the legacies of colonial religion, that is fair enough. But there are, across Indigenous cultures, assimilations of Christian stories and ideas, and I wonder what Kelleher in particular makes of this hybridisation (or co-existence).

Yunkaporta makes jokes about asking the deity for things, but I also can’t help thinking that calling out to ancestors to ‘open Country’ is like the orienting effect of prayer, which I think is closer to the original intention of something like the so-called ‘Lord’s Prayer’, rather than a Santa-ish wish list. For all its faults and historical distortions, Christianity as religion and site of ritual offers ways to orient oneself in the world, and it doesn’t have to be just a matter of waiting out this world for the next (a perspective that is rightly criticised). At the same time, Christians may find the challenges they make worth considering. All traditions need critique and re-orienting at times.

Yunkaporta’s critique of Christianity might best be seen in context of how his writing is meant to be part of ongoing dialogue, a process of yarning. Online he has said that he got things wrong in his first book, Sand Talk, and that he sees himself more as provocateur than expert. (In this, the permanency of print is perhaps inappropriate.) This is evident in his style, which in his books, seems, to me anyway, initially prickly, partly because of his reaction to the arcane and pretentious (in any tradition). But it becomes welcoming if one sits with it long enough.

One can sympathise with Yunkaporta’s impatience with spiritual thinking that he thinks is wrong-headed or cloudy. The authors recognise, when necessary, where traditions go astray and are negative, even their own. They warn against even Indigenous elders who want to mesmerise with obfuscation and who use tradition for their own advantage. (Be wary of snake-oil salesmen, they say.)

They write about the negative attitudes to women in Chinese-influenced Myanmar Buddhism. They write about how the Toltec empire may have collapsed because it became too top-heavy, with elites conducting rituals that became too distanced from everyday considerations. From an Indian friend Yunkaporta and Kelleher take the advice that inner calm comes not from retreat but from remembering connections in the midst of the busyness of life.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.