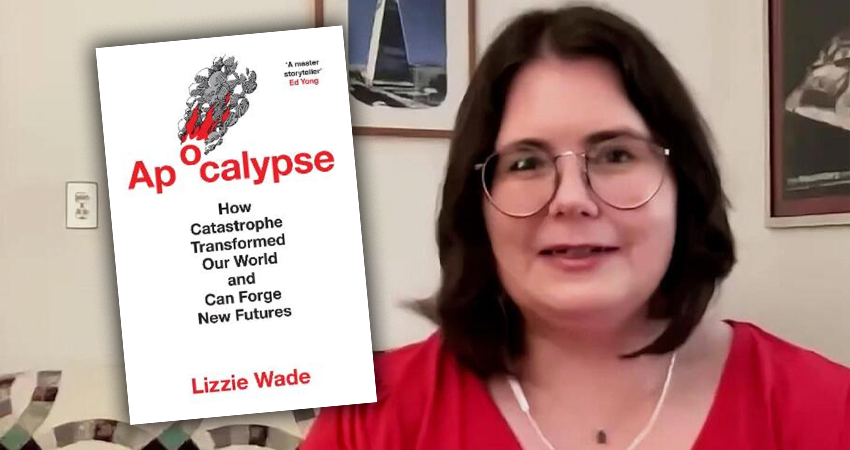

Review: Apocalypse, Lizzie Wade, William Collins

This book is about apocalypses and new beginnings, cities and civilisations collapsing and starting anew, of disasters and new worlds. We think of apocalypse as catastrophic ending, and Lizzie Wade describes it as such, but the book overall steers closer to the biblical and original meaning of apocalypse as revelation – as revelation of dark days ahead that will nevertheless lead to a transformed landscape and a new way of living.

Wade wants to show how life moves on, one way or another, after catastrophe. Although she doesn’t mention Jared Diamond, Wade warns that we should look past stories of collapse, of the kind that he tells, as lessons about hubris or incompetence, and look at what came next, through resilience and innovation.

In the 1300s, amongst, or after, the horrors of the Black Death, which arrived on top of decades of poverty and exploitation, there was one positive: the huge loss of life meant a loss of labour, and as it was in short supply, wages for workers rose, and exploitation became unthinkable. During the plague, somewhere near half of Europe died. Workers became more travelled. They could seek higher wages elsewhere in a workers’ market. This new prosperity meant the majority (of those who survived) lived better than their parents had. This might have been small comfort for those who had lost whole families, writes Wade, but it signalled improvement just the same.

This seeking of silver linings marks the various stories making up the chapters of Wade’s book. She writes about how, rather than being wiped out, Neanderthals were incorporated into the genes of their Homo sapien cousins, how communities on the coast of South America reinvented themselves with the waxing and waning of El Nino, how when the area between England and Holland was drowned people took advantage of the new, rich coastlines. Amongst this she speculates on what people thought as their worlds changed, using a lot of ‘maybe’s – she takes the time and space to imagine, to be evocative, to place herself in the shoes of our ancestors and to recreate landscapes and mindscapes.

Apocalypse is often thought of as societal collapse (though the death of the dinosaurs can also be thought of as a kind of apocalyptic catastrophe). Five thousand years ago, what may have been apocalyptic at the time – sea level rise – may have brought people together, to eventually form towns and cities. Societies became more stratified, and leaders may have taken advantage of hazardous conditions to promise stability. This transformation had its good and bad sides – Wade argues the complexity may, like our own society today, set us up for spectacular failure. In India, there is evidence of a grand city (Harappa) that, 4000 years ago, was hit by climate change which rapidly brought on collapse – from an apparently equitable and well-run society to violence and hunger.

In Egypt 4000 years ago, the Nile floods failed, as subsequently did crops, and the desert advanced on the river, an obvious catastrophe. But after the subsequent societal collapse – the end of Egypt’s Old Kingdom – rulers had to be more proactive in keeping the citizenry happy – in Wade’s words, they had to serve rather than being served, and there is archaeological evidence that citizens were better-off. One way, it seems, is that the rulers had to simply be less demanding, allowing people to run their own lives. One famous written account from a senior bureaucrat saw the collapse of the centralised state as a tragedy, but Wade looks past this to see the silver lining.

It’s not always the case. In the Caribbean, in the days of slavery, the hideousness didn’t allow for much an upside, but even there, archaeologists have found surprising evidence of ingenuity and defiance. In Mexico City, the most tragic of events have become distant memories, as ruins were built on and new cultures evolved, as Indigenous societies replaced older ones, the city was conquered by the Spanish, and modernity gradually buried the colonial empire.

Except water remembers, and Wade writes about the almost-farcical way Mexico City suffers from too much and not enough water – because the old water infrastructures were destroyed and paved over by the colonists, the city floods, but the aquifer under the city has been exploited and has receded, and the city has acute water shortages. Wade writes that present problems can sit on past apocalypses.

After the Black Death, it took the English ruling class fifty years to gain enough traction to exploit again. Wade warns that while England didn’t collapse, old inequalities were eventually re-established and reinforced. This happened repeatedly in Egypt, what Toby Wilkinson calls the most enduring state the world has known but one that was built on huge inequality, myth and ‘scant regard’ for human life. Colonial countries such as the US and Australia were built on the near-collapse of Indigenous societies, but they may be now facing their own eventual apocalypses. The question, for Wade, is less how it will end – and ends are inevitable – and more about what comes after: will it be renewal, or more of the same?

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.