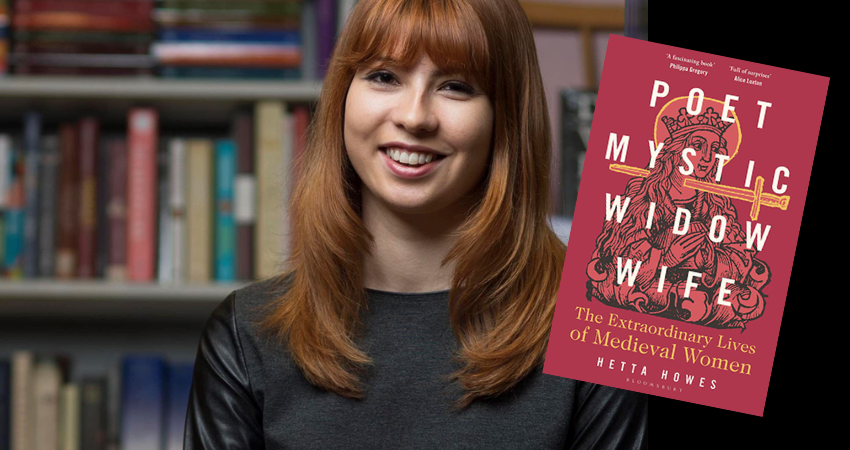

Review: Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife: The Extraordinary Lives of Medieval Women, Hetta Howes, Bloomsbury

In the Middle Ages women ate, drank, slept, made love, had babies, worked, danced, prayed. They were daughters, wives, widows, friends, lovers and mothers. Less commonly, they were mystics and poets. It was rare for them to write about their experiences, but some did, and got away with it, either because their writings were of religious or commercial value, they were high-born, they didn’t show anyone or they simply persevered.

Hetta Howes’ book is about four women who wrote about themselves or their times, illuminating the experiences of medieval women in general: Marie de France, Julian of Norwich, Christine de Pizan and Margery Kempe. She describes them as extraordinary, partly because they would be so in our time too, but also because they pushed hard for rights and acknowledgements that would become commonplace in our time but were rare in theirs (even if, as Howes writes, things are not always rosy for women in the twenty-first century).

Marie de France was born in the twelfth century, a time of significant and prolific court and religious writings, and Marie’s writings indicate a high level of education. Like Margaret Attwood, she took traditional tales and, from a gender perspective, turned them on their heads, showing that women didn’t always believe that they should take a back seat.

Christine de Pizan grew up in the French court but fell out of favour, and when her husband died, she paid the bills by becoming a prolific author and publisher. Her Book of the City of Ladies is a proto-feminist refutation of the misogyny of male writers. Christine wrote against men who thought women’s pursuits were lowly but then criticised women when they kicked against expectations.

Julian of Norwich is well-known; her position as an anchoress allowed her to have some influence. Howes, writing about Julian’s – to us perhaps – unusual enthusiasm for being locked up in a tiny room by herself for most of her life, is not dismissive of such medieval attitudes but understands how by contemplating Christ’s Passion, women could see their own bodies as both fragile and life-giving, and as something sacred.

Margery Kempe could be described as an English middle-class businesswoman who had a religious and traumatic experience after childbirth and thereafter took on a contemplative life, while still married, and preached at people wherever she went, including on pilgrimage. (Eventually she made it to Jerusalem, on her own, when such travel was suspect.) Most medieval women were wives or nuns – Margery’s story shows the perils of ‘trying to have it all’ – a problem as much today as then. Christine de Pizan thought herself ‘naturally inclined’ to scholarship but found she could only write when her son was abroad, and she was relieved of motherhood duties.

Margery was put in prison – for stirring up other women with her preaching. She travelled to Germany, gave her money away in Rome, made friends and was deserted by them, enraged people with her loud piety, but also inspired other women, including Howes, who admires Margery for her attempts at subverting expectations of women. (But it’s also hard not to come to the conclusion that Margery was also mentally imbalanced, perhaps post-traumatic. When her long-suffering husband fell down stairs and needed care, Margery had to be persuaded to tear herself away from contemplation to help.)

Margery was one of the first to write about childbirth – Howes puts this in the context of medieval understanding (or lack of it) of human reproduction and the Church’s views on it, including the legacy of the Fall, strange views on Mary’s virginity and motherhood and the conception of Jesus. Besides folk cures often being nonsense, childbirth was a dangerous business, and women were largely blamed for a lack of children (though the possibility of male infertility was understood), pregnancy was described in unflattering terms and there was much scaremongering aimed at women, though sometimes for the purpose of driving them to convents. There were more positive accounts; the days after childbirth were described as festive and communal by Christine de Pizan. Christine was a popular author who even wrote books on politics and the military, but she also wrote about how women and men have different, God-directed talents and places in society, and assumes men are better equipped to lead. Like men, she thought women needed to take on more ‘male’ attributes in order to lead, though she also praises more feminine traits that can be handy for leadership.

Her writings reflect the demarcations of gender but also indicate how women could rise above their status, but how just like today, negotiating such things can be complex, rewarding and fraught.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.