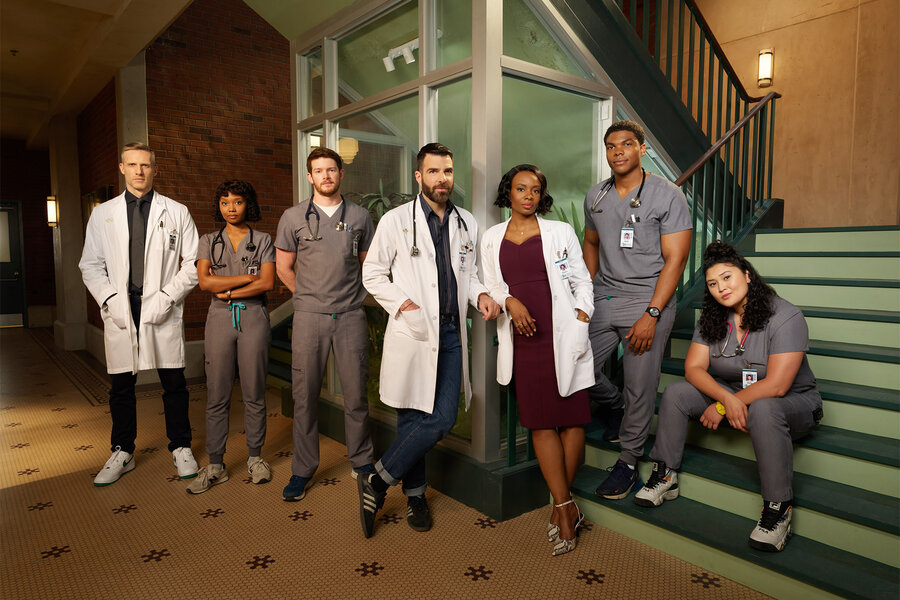

Review: Brilliant Minds

Medical dramas have long thrived on heightened tension—emergency room chaos, impossible diagnoses, and the occasional moral crisis. At their worst, they fall into formula: a “disease of the week” resolved by a heroic doctor just in time for the closing credits. HBO Max’s Brilliant Minds, starring Zachary Quinto, could easily have landed there. Instead, it offers something quieter, more humane, and more theologically interesting: a show about limits, compassion, and the dignity of seeing another human being.

Brilliant Minds is based on the life and work of neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks. While the series features a fictional character, Dr. Oliver Wolf, the cases, methods, and the show’s overall spirit are drawn from Sacks’ compassionate approach and his many popular books, which documented his real-life patients and their neurological conditions.

Quinto plays Dr. Oliver Wolf, a brilliant neurologist whose expertise is matched by his unusual vulnerability. Wolf lives with prosopagnosia, commonly known as face blindness. He cannot recognize even the faces of his closest colleagues or family members. Every interaction, whether with a patient or a co-worker, requires him to pay close attention to details most of us overlook—voices, gestures, mannerisms, posture. Where another doctor might rely on recognition, Wolf relies on attentiveness.

This condition could have been used as a gimmick. Instead, it becomes the heart of the show. Because Wolf cannot take recognition for granted, he treats each patient with extraordinary care. He listens more deeply. He notices what others ignore. He makes fewer assumptions. What could have been portrayed as a deficit turns into a discipline of compassion. And that is what elevates Brilliant Minds above the crowded field of medical procedurals.

Faith tells us that true recognition goes deeper than physical sight. The Hebrew Scriptures are filled with God’s reminder that He sees not as mortals see, for humans look on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart (1 Samuel 16:7). Wolf’s practice of medicine embodies this. His face blindness strips away surface assumptions, compelling him to recognize patients in their vulnerability, their stories, their pain.

Where many medical dramas thrive on ego—the genius surgeon, the rule-breaking maverick—Brilliant Minds insists on humility. Wolf cannot afford arrogance. His vulnerability grounds him, reminding both him and us that medicine is not simply about technical mastery but about human connection.

From a faith perspective, this humility feels profoundly vocational. Christian tradition often describes vocation not as a personal achievement but as a call to service. Wolf’s attentiveness to his patients is not glamorous. It is painstaking, even exhausting. Yet it reflects the kind of love described in 1 Corinthians 13: patient, kind, not self-seeking. His condition might be seen as a burden, but the series shows how it becomes a way of grace—a reminder that our limitations can also be our ministries.

At least one of Wolf’s colleagues voices this directly, seeing his face blindness not only as a challenge but as a gift. Because Wolf cannot depend on easy recognition, he offers a different kind of presence—one that goes deeper than appearances. The colleague’s perspective becomes a quiet theological echo: what looks like weakness can be strength, what seems like limitation can be gift.

The tension in Brilliant Minds is not just in solving medical puzzles but in the simple human challenge of recognition. Patients want to be seen. They want to know their doctor remembers them. Wolf must find ways to communicate that recognition, even when he cannot depend on his eyes.

This struggle mirrors something deeply spiritual. In communities of faith, recognition is central. We want to be known by name, welcomed at the table, not overlooked or dismissed. The danger in both medicine and ministry is treating people as cases or problems rather than as beloved children of God. Wolf’s discipline pushes him—and us—to resist that temptation. His inability to recognize faces becomes a radical form of spiritual training: to look past surface, past labels, into the fullness of a person’s humanity.

Where other shows get bogged down in melodrama, Brilliant Minds often pauses for tenderness. A patient is not simply a carrier of symptoms but a whole person, fragile and complex. The series allows room for compassion to breathe. This is its theological strength: it reminds us that healing is not only about curing but about care.

For Christians, healing is never just physical. Jesus healed bodies, but also spirits and relationships. He restored people to community. In its best moments, Brilliant Minds gestures toward this holistic vision. Wolf’s care for patients is not limited to their medical charts. It extends to their fears, their dignity, their longing to be recognized.

Zachary Quinto brings both intelligence and gentleness to Dr. Oliver Wolf, grounding the character in credibility and warmth. But what makes Brilliant Minds memorable is not just his performance. It is the show’s refusal to treat vulnerability as a liability. In a television landscape crowded with medical prodigies and miracle cures, Brilliant Mindsdares to suggest that true healing begins with attentiveness, compassion, and recognition.

This is nothing less than gospel truth. To see another person—to truly see them—is to honour the image of God in them. Wolf may not recognize faces, but he recognizes humanity.

Season 1 of Brilliant Minds is now on HBO Max.