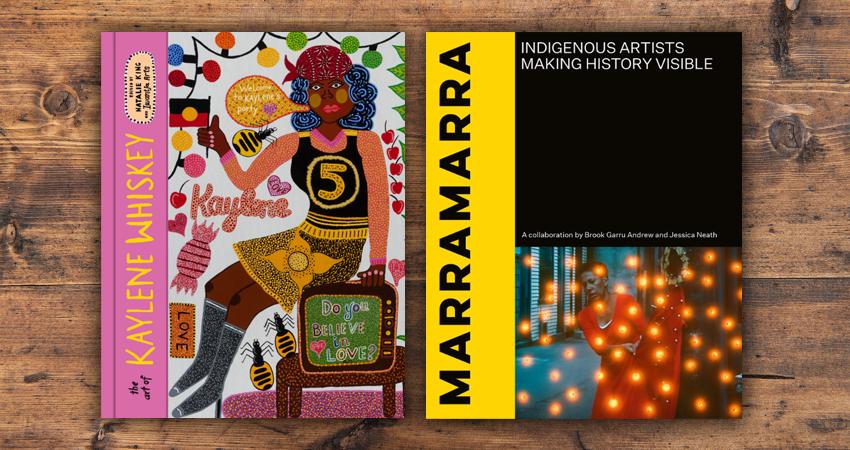

Reviews: Marramarra: Indigenous Artists Making History Visible, Brook Garru Andrew and Jessica Neath, Newsouth and The Art of Kaylene Whiskey, Natalie King [ed], Thames & Hudson

The idea of Indigenous art may call to mind more traditional artforms, but Indigenous art continues to evolve. There are many Indigenous artists reinterpreting culture through modern forms and media. The book Marramarra is a global sample of how artists, through both modern expressions and the resurgence of traditional forms, are addressing the legacies of colonialism and some of the urgent issues of the present and future.

The book is centred on the Australian Indigenous experience but reaches out beyond our shores. It is a mosaic work but structured around five chapters relating to specific artworks and artists that address particular themes, both the difficult and the celebratory – loss of land and genocide, but also connection to land, community and the power of remembering. While Indigenous artists engage in the practice of truth-telling, this is part of a process of clearing and cleaning, in order to look at better possibilities.

Artists are uncovering, against the repression of truth about deaths and the destruction of culture and attempts to cut the threads of memory and connection to land. In California, an artwork that mimics the Hollywood sign but proclaims ‘Indianland’ points to the theft of land that allowed the movie industry to flourish. Many artists are challenging museums, which would seem to be keepers of memory, but which have participated in the distortion of history and the disempowerment of Indigenous people.

Unavoidably, Indigenous history is entwined with other issues – climate crisis, war. Global Indigenous approaches to land, expressed through artwork here, offer alternatives to destructive attitudes. For Indigenous peoples, the land is so important that it cannot be thought of as possession, an unhealthy flipping of the relationship. Occupation and recognition of that occupation are different to ownership. Marcia Langton, Australian Indigenous scholar, writes of it as ‘homeland’ – the idea that sovereignty means an attachment to place.

This means that care and sustainability, rather than utility, are embedded in traditional culture (and expressed in art). In Alaska, Indigenous tribes are suing the government for denying them subsistence rights while overseeing the decline of waterways. One Australian artist points to the much-needed wisdom of elders who know how to care for land, while politicians spin and talk of continuous and clearly unsustainable plunder.

For many artists, it is important to emphasise language. While artworks can convey knowledge without written language, using Indigenous language, even with English characters, highlights how language is a repository of knowledge and how it brings communities together and perpetuates culture. (This is why colonial powers often forbade traditional languages.)

I note the deliberate impermanence of some artwork recorded here – art used in ceremony and temporary earthworks, performances. These not only draw from the importance of ritual but also illustrate in a way the ebb and flow of life, the impermanence of things generally, the importance of relationships, the subsidence of individual action into community memory, and how art is not just locked away in sterile gallery spaces.

Indigenous artists emphasise how the often-highbrow business of art is inseparable from everyday life. This comes out in intriguing ways in the eye-popping art of Kaylene Whiskey, whose art is celebrated in this new monograph from Thames & Hudson. She explores ‘identity from the perspective of lived experience’, in the arty words of her editor.

Whiskey mixes portrayals of inspirational (largely) female pop music figures with features of her life in her so-called remote community in South Australia. Her art has obvious similarities to Vincent Namatjira, who lives in the same community, to American folk artists like Grandma Moses and even to Frida Kahlo, but Whiskey’s art is more whimsical and bedazzled. She takes the dots of traditional Australian art, just as delicately rendered, and uses them like the sequins she favours, but there is a confident, balanced precision that pins down what otherwise might be an overwhelming riot of colour.

There are endless variations on a sparkly theme. Cher, Tina Turner and her favourite, Dolly Parton, rub shoulders with insects and lizards, desert flowers and Coca Cola bottles, love hearts and party foods (both junk and bush foods). She uses speech bubbles, as if making comic books, but unlike comics, here everything is happening at once. The flatness of the picture plane and the varying proportions suggest the all-at-once storytelling of religious paintings. For Whiskey, it is more like being at a party, where she and her friends are dancing and feasting and dressing up. But this is not mere superficiality.

It all adds up to a celebration of friendship, Indigenous concepts of family and, most importantly, strong women who, as Whiskey says, show that strength through love toward others. Mixed with this is humour: Tina Turner ‘noodling’ (looking in the tailings of opal miners) for opals (as Whiskey did when she was young, perhaps initiating her portrayals of glamour in the outback), an ‘I love KW’ tattoo on Tina’s leg, honey ants stealing party food, Whiskey saying that if Dolly Parton visited, she would first ask her how she takes her tea, then show her the community’s ‘beautiful’ little church.

Her editor points out that, in her paintings, Dolly and co. visit Whiskey, not the other way around, so that both fan and singer are on equal footing. Central Australia becomes truly central to her vision, and there is something about putting these figures into her world that de-exoticizes it. At the same time, she paints a utopian everywhere where, she says, all are welcome.

Sometimes she paints figures over old photos of the outback, putting Aboriginal people back into landscapes deliberately emptied. These figures are usually celebrating, dancing, singing – her focus is on love and joy, which is the equally important flipside to recognising historical legacies and contemporary problems.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.