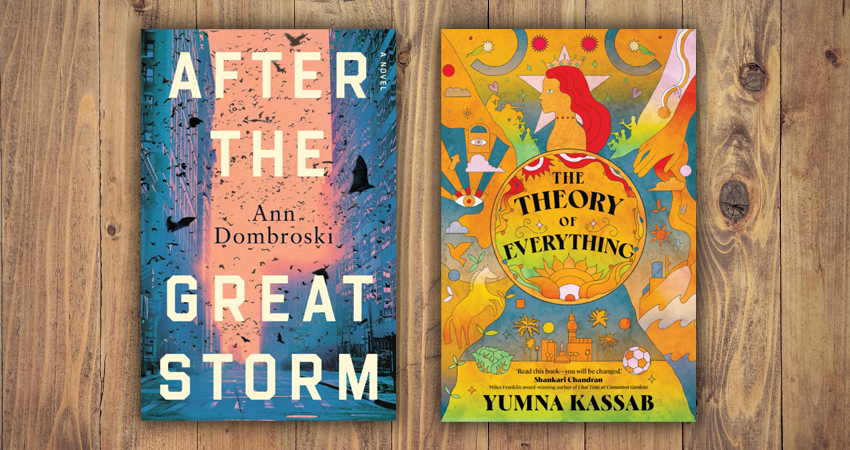

Reviews: After the Great Storm, Ann Dombroski, Transit Lounge & The Theory of Everything, Yumna Kassab, Ultimo Press

Here are two Australian novelists pushing the boundaries of fiction, playing with format and narrative, but also using fiction’s flexibility to make moral points about difference and welcome.

Ann Dombroski’s book has some similarities to recent dystopian fiction, being set in a Sydney fifty years in the future, where damaging storms are frequent and the city is more fragmented. Life is different but the same: there are self-driving cars and quantum computers, Australia is a republic, more of the city’s services have been privatised, which is therefore causing inequalities, drugs to reverse the ageing process are available to those who can afford them. People are concerned about work and family, on TV people are watching a mission to Mars, which of course is broadcast constantly like a reality show.

The protagonist, Alice, works in the medical industry, and has a husband in jail, accused of terrorism on the city’s transport system. She is trying to prove his innocence and that he is a scapegoat. Meanwhile, a fugitive from a strange medical experiment lands on her doorstep, disoriented, injured and ill.

This person is a kind of batwoman, symbolic and symptomatic of the process of scientific experimentation proceeding because it can, not because it should. She is also symbolic of otherness, of the minority, of race or ability or sexuality, not as a distorted humanity, but as someone who may be different to the mainstream and might need extra care, not ostracization. Alice, while at times resentful of the role she has found herself in, on top of work and trying to extricate her husband, is caring, whereas her neighbours are suspicious, fearful, and we might see here parallels with current arguments over identity, conformity, prejudice and care.

Issues of difference are also prominent in the work of Sydney writer Yumna Kassab, especially in the experience of migrants and women. She has been churning out her sometimes fable-like novels at an impressive rate; this latest one has the flavour of the carnival coming to town.

The blurb on the back of the book doesn’t really help much. (The novel is ‘fantasy, humour, a romance without any leads, a defiance, a subdued rebellion…’) But it is more invitation. The book is a dizzying conglomeration of stories and experimental writing. It’s like Kassab is trying to cram in every writing style she can think of (and, oh, has she mastered them all!). To use a sporting metaphor – since she writes about soccer – there are short plays, she attacks the goal from every angle, she switches to keep things lively, there are punchy moves, part of an intricate, overall game plan.

Earlier on there is a story of a young female soccer player, daughter of a famous male player, who is facing gender and culture expectations. Through the story, Kassab explores, beyond the esoteric nature of sporting success, issues of loyalty – to club, country of origin or arrival, to culture, family or oneself – how there is a tension within migrants between the desire for a better life and guilt over leaving, and how being a famous Muslim sets up public expectations and assumptions.

On the topic of gender, she writes about prejudice, hypocrisy, love, clandestine abortion, desperate mothers, silence, global inequalities, violence against women, body images and fear. Another longer piece is about an actress, Lucille, who is residing in a hotel in retirement and who is a symbol of expectations on women, even from oneself, and the relationship between the inner self and the persona one projects in public.

There are shorter pieces like poetry or simply lists of aphorisms and mantras. There is acerbic commentary on the ugly duckling story, amongst half-page stories about toll roads and crashes and hordes of children. She aims for the rotten heart of modern life: consumption and vapid entertainment, disconnection – from each other and nature – and our preference for simulacra over the real.

In the last story of the book, she writes about holidaying and befriending a vampire (!), and about the modern (perhaps perennial) desire for order and summary, against the reality of life being chaotic, conflicted and open-ended, a view that is certainly underscored by her dazzling, kaleidoscopic style.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.