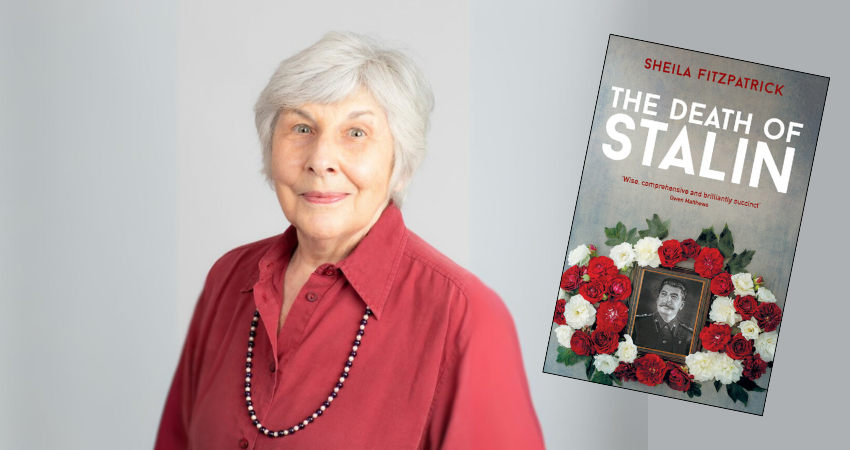

Review: The Death of Stalin, Sheila Fitzpatrick, Black Inc. Books

Joseph Stalin’s death was something of a ‘black comedy’, writes Sheila Fitzpatrick, and, indeed, it is treated as such in the 2017 film that shares its name with Fitzpatrick’s book. By 1953 Stalin was aged and was in the habit of subjecting his colleagues to all-night dinners at his country house, where he now resided, and to rambling phone calls during the day. Until one day they suddenly stopped.

Stalin had many bodyguards and servants, but all were too sacred of him to enter his room to check on him when he didn’t emerge. Finally, his housekeeper was sent to check: Stalin had had a stroke. His four closest colleagues got him back into bed and returned to Moscow. When his reluctant doctors established Stalin was dying, his colleagues quickly worked out a succession plan, approved by state and party organisations while Stalin was still hanging on.

As his body lay in state after he died on March 5, classical musicians played and crowds came (including a young Gorbachev), as much for the spectacle as to mourn. A hundred people were killed in a crowd crush. The Soviet Union went into mourning; the rest of the world sighed a sigh of relief. Both within and outside the Soviet Union, there was hope of a thaw. There was genuine grief in the Soviet Union, but for what wasn’t clear. Stalin was like a god, he was a father figure, he was a feared dictator. The grief was like shock for some.

Fitzpatrick uses the death of Stalin as an entry point to discuss his leadership and reputation in this short book, which shows all the ease with the material, compression and readability of her recent The Shortest History of the Soviet Union. Of course, this leads eventually to evaluating his place in the history of the USSR which Putin is recreating.

While citizens wondered how Stalin should be memorialised, officially he was dropped like a hot potato, in stark contrast to when Lenin died. A million prisoners were freed from the gulag system and Stalin’s cult of personality was dismantled; Khrushchev’s surprising 1956 repudiation of Stalin would stun the USSR and the world. Stalin’s body was removed from Lenin’s mausoleum.

What did his death mean internationally? At the time, there was new academic interest in totalitarianism, and so much scrutiny of the USSR, but the West was unsure what would happen next. Soviet leaders knew they couldn’t compete in war with the US. President Eisenhower, realist that he was, wanted to avoid war, and was interested in peaceful overtures. Unfortunately, he was distracted by golf while his diplomats escalated the Cold War.

It was a tale of mutual misunderstandings. Both sides assumed the other wanted war and couldn’t be trusted. The Soviet leaders hinted publicly after Stalin’s death, loudly enough, that they wanted peace, but the Americans assumed it was just bluffing. It wasn’t like the Soviets were innocent, but anticommunism had become a non-negotiable core American value, while there were sectors of the Soviet regime that were just as suspicious of the Americans.

Once Khrushchev was ousted by Brezhnev, largely an outcome of events in Cuba, Stalin’s reputation was not rehabilitated but Brezhnev would wind back some of the loosening that Khrushchev had initiated. Despite what the West thought of Stalin, or perhaps because of it, he continued to have fans in the USSR, who thought him a better leader than the succession of buffoonish or sleepwalking leaders after him. Gorbachev was wary of stirring up controversy by mentioning him. It would be Putin the arch-patriot who would praise Stalin for nation-building and winning the war.

After decades of chaos, ordinary Russians now report admiration for Stalin (while younger Russians know little about his bad side). In Ukraine, Stalin is, naturally, a great villain; in his native Georgia, he is remembered more reverently, but his reputation is declining there – he is remembered as Russian as much as Georgian. For various reasons, he literally haunts the dreams of Georgians, enough, says Fitzpatrick, ‘to warrant a special scholarly article on the subject’.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.