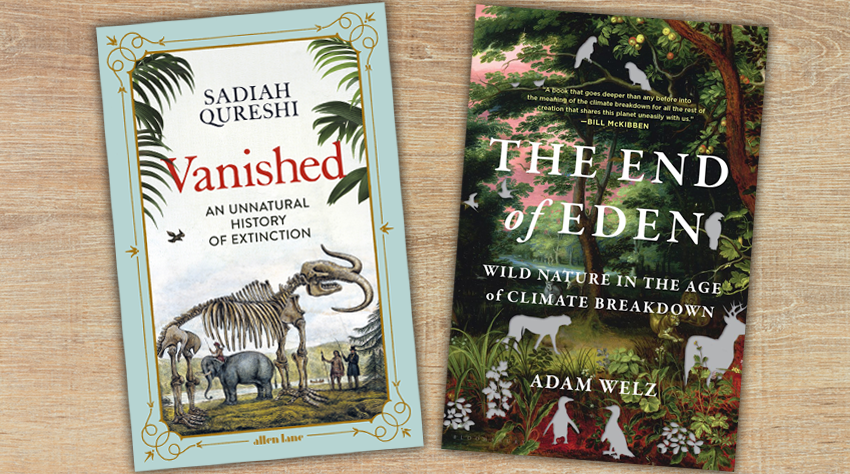

Reviews: Vanished: An Unnatural History of Extinction, Sadiah Qureshi, Allen Lane/Penguin, The End of Eden, Adam Welz, Bloomsbury

Extinction is a fact of life on Earth, but it is only recently that we have recognised the potential for humans to cause extinction. Previously, nature was seen as so vast as to seem inexhaustible. But there is evidence that humans may have been at least partly responsible for the extinction of all manner of megafauna at the end of the last Ice Age. That is still debated, and it is also debated whether our current moment can be classed as a sixth mass extinction, but it is certainly clear that human modification of the world is making many species extinct.

In her book, Sadiah Qureshi brings up the ethical issues around extinctions, not just in terms of how humans are dominating non-human species to the point of extinctions, but in the legacies of colonialism that are entangled with notions of extinction and conservation.

Think of extinction and we might think of the dodo or the dinosaurs, but once the idea of extinction had been accepted, there was debate over the potential for people to become extinct. Of course, an ethnic group is not the same as a species. Nevertheless, for example, Aboriginal Tasmanians still have to deal with the legacy of colonial powers deciding at one point they were extinct.

In the North American colonies, Native Americans were talked about as facing extinction – deliberately, through schools where native culture was outlawed, and inadvertently, pushed out of sight, even treated like endangered zoo animals. In the US there were suggestions Native Americans be retained in large national parks. Those parks, in the end, were created as if Native Americans had gone extinct. Even when employed as guides, the assumption was that they ceased to be the legitimate occupiers. As Qureshi writes, they vanished, even while still being visible.

Qureshi points out how once extinction was established as a recurring part of deep history, as a part of the survival of the fittest, Indigenous peoples were viewed through this lens. Fears of extinction hurried those bent on Christian conversion of Indigenous people; elsewhere extinction could be conflated with extermination. As soon as you talk of natural decline due to competition, the greed and cruelty of colonialism and invasion is justified as just the normal course of events – the will of God or the natural course of evolution. Evolutionary theory’s founders Darwin and Wallace both contributed to this view.

Moving to the twentieth century, Qureshi notes the happier tale of whale conservation, which seemed to prompt other environmental concerns. Sure, the wholesale slaughter of whales, which continued after the world wars, was lamentable, but the plight of whales was one of the most prominent cases of humans realising that the natural world is not an inexhaustible set of resources, and that preservation must keep pace with technological advancement. Whale numbers may be healthier again, but just when global temperature rises are affecting oceans, and there are worrying precedents from previous mass extinctions of what happens when temperature rises cause flow-on effects of food chain collapses and the likes.

The sheer quickness of temperature rise, in geological terms, means animals and plants have no time to adapt. On the east coast of the USA, Adam Welz explains in The End of Eden, a one-and-a-half-degree temperature rise means swathes of destruction, but less obvious to the casual observer than, say, the aftermath of a hurricane. There is a pine beetle that has been marching up the coast and decimating hard pine populations. Previously it had been hindered by extreme winter temperatures. There is a blight from Asia that has effectively made extinct a North American chestnut – one that, ironically, the now extinct passenger pigeon used to rely on.

In Kazakhstan recently, 200,000 Saiga (a type of antelope) died after bacteria in their systems had suddenly multiplied during unusually humid weather and poisoned their blood. ‘All it took was a few days of strange weather,’ says Welz. Across bird species, migratory birds are being knocked off kilter by even small seasonal changes that affect food sources, including insects, which are in dangerous decline. Plants, too, feel the effects, of course. In the 2020 Australian fires, eucalypts, which are well adapted to fire, could not cope with the dry and then extreme heat of the fires, which burned wood as well as leaves, leaving a blasted landscape.

Habitat loss compounds things. In 2017 Hurricane Maria wiped out a flock of Puerto Rican parrots. You’d think they’d be used to hurricanes, but the trouble is that the birds, once widespread, had been forced into a last refuge by land clearing; unfortunately, this small patch of hilly rainforest was especially exposed to the ferocity of the storm. There was nowhere to go, and no widespread population to absorb the losses.

We might wonder, perhaps, why nature is so sensitive, but life is adapted to stable environments, making for wonderful biodiversity. Diseases often thrive when things get out of equilibrium, and this is a warning – or, since we don’t seem to heed warnings very well, a vision of the future: it doesn’t take much to create massive instability that leads to extinctions.

Qureshi writes about the two solutions: conservation and de-extinction, Jurassic Park-style, each not without their complications. The science writer E O Wilson once suggested setting aside half of the Earth’s land area for wildlife – seemingly a noble if over-ambitious target, but Qureshi wisely wonders about which humans would be displaced. Usually, as in US history, it is Indigenous peoples, who already face pressure from the environments around them being compromised by development. The first preservation societies were formed to preserve big game for hunting (an oxymoronic pursuit, it would appear from our modern vantage point), something that necessitated pushing local people off their traditional lands. As Tyson Yunkaporta also observes, management of previously Indigenous lands is often still done on colonialist terms.

The dodo, the mammoth, the passenger pigeon, the thylacine (which Qureshi mistakenly announces is a recent arrival to Australia – she is thinking of the dingo, perhaps) – these are the candidates for de-extinction, with their resurrection justified by the dubious argument that de-extinction would encourage altruistic feeling. It’s possible it might do the opposite and make us less concerned about creatures going extinct while trusting in the power of technology to fix everything, reflecting the ambitious anti-greenhouse tech proposals that would minimise our need for reducing emissions. Rewilding may be a less extreme option, and workable in small quantities, but the question remains of who benefits, and, as Qureshi says, it is complicated by the question of which lives we value more.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.