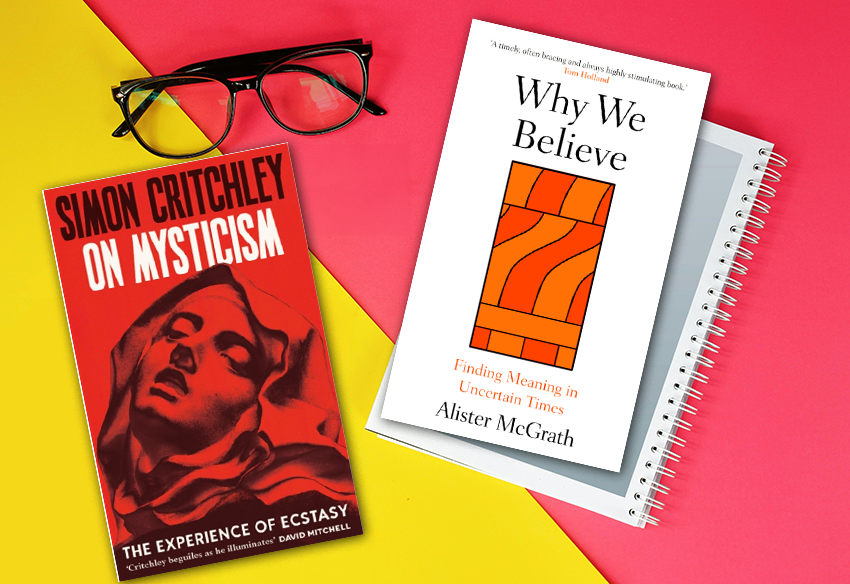

Reviews: Why We Believe, Alister McGrath, Oneworld | On Mysticism, Simon Critchley, Profile

In his latest book, Alister McGrath returns to his battle with the New Atheists, which may seem as dated as interest in Britney Spears’ personal life, but his point remains that people need meaning and story, not just facts – not as alternatives to facts, but as frameworks to make sense of facts.

Influenced by philosopher Mary Midgley’s ‘non-reductionism’, he argues against thinking of reality as only what can be scientifically measured, and that religion provides a structure for working through questions such as why the universe is here, if there are things beyond the material, what the point of my life is, what makes for human flourishing, and so on – questions that can’t be answered by using a microscope or telescope.

He draws on his own experience of a background in the sciences of chemistry, quantum physics and biology, and a flirtation with atheism. The writings of Bertrand Russell, of all people, encouraged him to see that we can believe things without there being irrefutable evidence – in fact, we must, otherwise we get nowhere, intellectually or in everyday life. We all, atheists included, hold beliefs shaped by the communities we are embedded in and make assumptions about the way the world is structured.

Science is excellent in its place, and provides extraordinary insight, but it doesn’t necessarily provide meaning. For some, of course, science suggests there simply is no meaning. For the more open minded, agnosticism seems logical, but McGrath thinks this is too equivocal. For him, religion at least points to answers to the biggest questions that can’t be answered irrefutably. (In contrast, religion fails when it tries to be science, like Creationism.)

Meaning subsequently gives direction on ethical behaviour – not the exclusive realm of religion, to be sure, but it helps. McGrath is keen to draw attention to the fact that belief motivates action, religious or not. Religion is not just a set of principles one agrees on. In Christianity’s case, it is not simply a matter of affirming everything in the Bible (which not all Christians do anyway), but a communal lifestyle with a moral purpose shaped by religious teachings that make a certain amount of sense.

Religious belief is often compared blithely to belief in the tooth fairy, but there are varying degrees of self-criticism amongst the religious. Believers make judgements, test arguments. Religious beliefs are a spectrum, and we do need to examine them. For someone like G K Chesterton, belief is testable in a philosophical way – a hypothesis that can be examined and, for Chesterton, makes sense of the riddle of existence. One can reject Chesterton’s and other believers’ conclusions, of course, but there is a philosophical logic there.

McGrath makes a sensible case for sensible belief, but there is an entirely different side of belief, under the term of ‘mysticism’, that philosopher Simon Critchley explores in his book, and that, to be fair to McGrath, McGrath at least acknowledges. Critchley apologises for an earlier distrust of mysticism, and here argues for an overturning of received ideas about mysticism, including that it is an outdated notion or philosophically impenetrable.

Critchley is not a believer in the mainstream religious sense, but he is an enthusiast for mysticism, describing at length the life and writings of Julian of Norwich, as well as touching on some modern writers who bring the mystical into their work – T S Eliot, who, in his poetry, describes the shock of revelation, and Annie Dillard, who insists the writer must be enflamed like the mystic. Critchley also writes how, these days, the music lover is akin to the mystic – an argument that may or may not seem a stretch.

The word ‘mysticism’ is something of an anachronism, a term Enlightenment philosophers used for something they were suspicious of, but which was widespread in the medieval church. Those we now call mystics just thought they had intensely spiritual experiences. They thought they were seeing into the heart of reality, but beyond the visible world. Primarily, they sought to lose themselves in their contemplation of God, which yielded all manner of paradoxical talk of what this entailed.

The problem with writing about the mystical is that mysticism pushes at the boundaries of language. We see this in the sensual descriptions from Teresa of Avila, and, in Critchley’s book, in the use of phrases like ‘Mysticism is a learning of the practice of unsaying, an unsaying which must continually and excessively be said, and which, by saying more, says less’. Critchley writes that writing about mysticism, as opposed to just writing about mystics, is like coming up against a great wall: mysticism is about experiences beyond words, something that trying to climb the wall of Critchley’s prose might confirm.

Yet, mystics didn’t see themselves as irrational – they are just contrary to a modern, narrow view of the rational. And a mystic such as Julian spilled much ink on trying to explain mysticism to others – and not just explain it but encourage others to cultivate it.

Here’s one of the paradoxes: while mysticism entailed intense experiences, the idea was to lose the self, so that the experience wasn’t happening to anyone in particular. Mystics aimed for an annihilation of self – whatever that might mean – and incorporation into God so that both the self and God ceased to exist in the manner that we usually assume.

No wonder this was sometimes challenging for church authorities. So, mystics were intensely scrutinised for signs of heresy. But this is not to say they were marginalised and secluded. Critchley notes that at various times mystics were wildly popular – with the laity, at least. And the Church itself could hardly criticise spectacularly intense devotion to God and that very Christian notion of selflessness.

Contemporary accounts of mysticism emphasise the moments of revelation and ecstasy, but Critchley points out that mysticism encompasses not just those moments but also years of later trying to understand those moments. Strangely, mystics can teach the religious how to persevere while the spiritual seems mundane, and God distant.

Last, Critchley emphasises that mysticism, unlike perhaps its caricature, is a physical, bodily affair, yet the point of this experience is to dissolve the distance between oneself and God, in, perhaps, the same way music moves us bodily, and we can be said to lose ourselves in the music. In medieval Christian mysticism there is an extraordinary amount of contemplation of blood, pain and death, a visceral experience that, at the same time, points to an asceticism that orients the mystic towards God and away from the distractions of the material world, all in order to, as Critchley notes, engage the heart, rather than just satisfy the intellect.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.