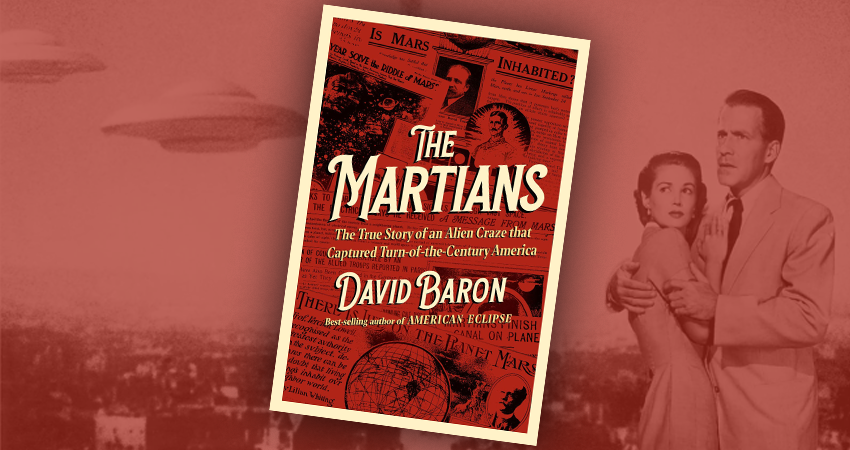

Review: The Martians, David Baron, Liveright Publishing

Had you been an American living at the turn of the twentieth century, you may have believed, incredibly, that there was intelligent life on Mars, confirmed by astronomers who observed geometric canals on the planet’s surface and popularised by the newspapers, and that efforts were being made to contact the aliens. The story of this Martian craze is described in David Baron’s delightful book, where characters such as Theodore Roosevelt, Alexander Graham Bell and Nikola Tesla appear as if in a Michael Chabon novel, and where the Martian craze has some parallels with our own time.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it was commonplace to imagine other planets inhabited. Later, such ideas seemed naïve. (They would be revived in twenty-first century discoveries of exoplanets.) But some clung to hope, and when new speculation about Mars emerged, the popular press loved it. Joseph Pulitzer – ironically, considering the prize that would later be attached to his name – would start a Murdoch press-style newspaper, and in 1892 it seized on reports of lights on Mars, observed through a new state-of-the-art telescope in San Francisco, to dangle in front of readers the proposition that there might just be intelligent life on the red planet.

Initially, this sensationalist light entertainment was picked up by other papers. Then, as 1892 was a good year for observing Mars (which has an elliptical orbit taking it variously closer to and further from Earth) and its so-called ‘canals’ that had been observed previously by an Italian astronomer, select amateur astronomers claimed to confirm their existence. Newspapers like Pulitzer’s did the same. After-all, the gas giants proved inhospitable, and Venus too hot, but Mars had some semblance of an atmosphere and, as far as they could tell from a reflective area at the pole, water.

In the context of evolutionary theories, it was speculated that Mars was ‘ahead’ of evolution on Earth – that explained its dried-out state – and its inhabitants had devised a planet-wide system for irrigating its surface, though the ‘canals’ visible from Earth were probably wider areas of cultivated vegetation. Percival Lowell, a wealthy Bostonian astronomer who was the most prominent advocate for life on Mars, and Baron’s main protagonist – if not tragic hero – saw not only canals but seasonal movement of water. He organised a special expedition of an American crew and telescope to South America, where, they claimed, they had further photographic evidence of canals, subsequently published in a prestigious magazine.

While not everyone could actually make out the canals in the tiny photos, the likes of the inventor Nikola Tesla agreed they proved Powell’s theory. The New York Times, no less, was eventually persuaded to announce, ‘THERE IS LIFE ON THE PLANET MARS’. Popular discourse was filled with references. There was a comic series in newspapers profiting from the conceit that a Martian had arrived on Earth and was discreetly observing the strange customs of Earthlings; even politicians made their points with references to Mars and Martians. The discovery of the reality of life on Mars was in the same category as the flights of the Wright brothers.

The next step was contact, and there were so many wonders being invented that contact with Mars seemed no less feasible. If anyone could send a message it might be Nikola Tesla. Tesla already suspected he’d heard from them, through his new-fangled electrickery, and announced as much in New York, where his enormous laboratory was based. He proposed broadcasting radio waves back at Mars. (Other schemes included large arrays of mirrors to flash signals into space.)

Mars itself was imagined, at first, as like the Middle East or Mediterranean, with oases of palm trees, then more futuristically. As to the appearance of the Martians themselves, they were initially depicted as simply human, but as speculation intensified, scientists on Earth noted that human anatomy is shaped by conditions here, and the Martians, though still humanoid, developed non-human characteristics influenced by Martian conditions, such as long proboscises. One theorist thought the dry conditions might produce ant-like creatures – the origin of artists adding antennae to their depictions of otherwise humanoid beings. A play, ‘A Message from Mars’ seemingly introduced the concept of green Martian skin.

H G Wells thought it was naïve to perceive Martians as humanoid, and he famously came up with a terrifying vision of malevolent aliens as vicious as nineteenth-century European colonial powers, who were observing Earth (and making plans for conquest), just as humans were intensely scrutinising Mars. Wells, who studied under Thomas Huxley, was inspired by evolutionary theory in imagining what the aliens would look like. He took some liberties in his fiction, of course, and later, inspired by more enlightened visions of interplanetary brotherhood, he suggested the real Martians might be like us, but with bigger heads (more developed brains, you see) and perhaps fur to protect them from the harsh Martian climate.

In another Edwardian rendering, Martians are gazing at a kind of cinema screen, observing life on Earth; they are like neoclassical angels, nude and with wings and headbands of flowers. This is intriguing, considering later conflations of the alien and the supernatural, in religious cults that believed in heaven-bound UFOs or benevolent aliens who would show us a brighter moral future. In a climate of what philosopher Charles Taylor would famously describe as disenchantment (yet at the same time as people felt ‘anything was possible’), the illustrations show clearly that belief in angels had transformed into belief in Martians – but like a transition specimen, the Martians still looked a lot like angels.

Life on Mars provoked all kinds of ‘religious contemplation’. The planet showed evidence that all its people worked together on a planetary scale, making its name – derived from the god of war – ironic, and providing an example to squabbling human tribes.

Not all scientists bought into the hysteria – many scientists remained unconvinced. Sceptics said the canals were an optical illusion, as they turned out to be: the brain sometimes creates patterns from the random features the eye sees. The astronomical society was having none of it – photos of Mars from ever larger telescopes increasingly showed there were no canals – and it printed dismissive statements in newspapers. The spruikers of canals seemed increasingly foolish, though, writes Baron, their legacy was to inspire sci-fi writers and aspiring astronauts.

People believe what they need to, and fit evidence to their beliefs. Lowell’s insistence on canals and his devoted following amounted to a ‘pseudo-religion’, writes Baron. Interestingly, he notes that American freethinkers thought that if alien life was proven, this would discredit Christianity; this was partly why the canals were so tantalising. But Christian theology proved more flexible, with clergy happy to accommodate the Martians and jumping on the Mars bandwagon themselves. The contemporary craze for spiritualism also became entwined with the enthusiasm for Mars, with various claims of having astral travelled to the planet to meet its inhabitants.

Though the Martian craze seems almost unbelievably strange now, it has parallels with current obsessions. The scientific establishment a hundred years ago complained, as it does now, of sensationalist pseudo-science peddled by popular media. Self-proclaimed experts marshal evidence with some basis in science to prop up the most intricate and radical hypotheses that they legitimate by saying that proof will be forthcoming or that the hypotheses are simply ‘beyond doubt’. Dreams of Mars colonisation by tech billionaires are driven by visions of utopia offworld. Existential loneliness provokes longings for extraterrestrial beings. Astrophysicists, having discovered thousands of exoplanets, talk, convinced, of life on these planets, even if that is simply an inference, a contemporary case of seeing canals where, at present, we have no evidence they exist.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.