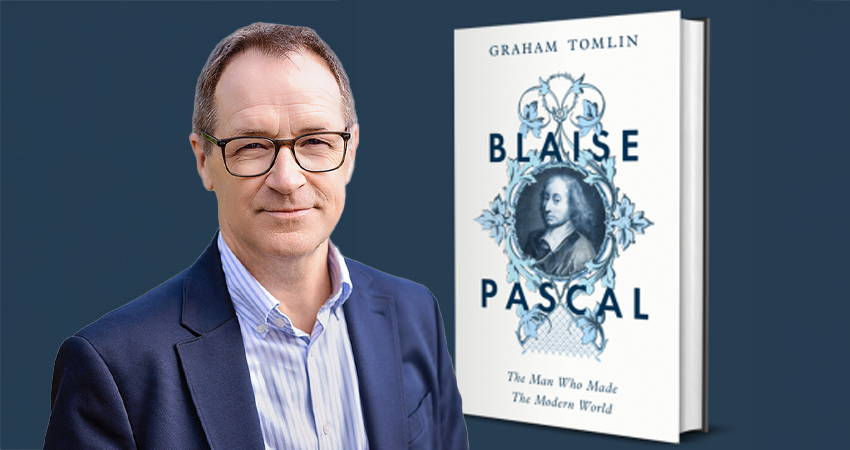

Review: Blaise Pascal: The Man Who Made the Modern World, Graham Tomlin, Hodder

Seventeenth-century polymath Blaise Pascal is now most famous for his thought experiment dubbed ‘the Wager’, whereby he argues that it’s a good bet to have faith in God and potentially avoid eternity in Hell, rather than bet on there being no afterlife. If you bet on God, and there turns out to be nothing there, you lose little in this life, but if you bet against God and there is an afterlife, you stand to lose a lot. Therefore, you should bet on there being a God. This at least is how it is popularly remembered, and there have been many criticisms of it; it might not be surprising that, as Graham Tomlin argues in this biography, the summary above is not quite what Pascal, a subtle and innovative thinker, had in mind.

Pascal was born into the age of microscopes and telescopes, Louis XIV, the Jesuits and the Counter-Reformation, discovery of the ‘new’ world, humanism, the Renaissance and the sudden obsession with the self (as noted by philosopher Charles Taylor). It was the age of Descartes’ ‘reasonable’ Christianity, and Tomlin patiently lays out how we can’t understand Pascal without understanding how Pascal’s thought is situated in all this.

Pascal’s life featured a mix of the odd and miraculous events and an interest in what we now call science. His father, part of a new class of nobles, who mixed in circles where priests discussed maths and philosophy, gave Pascal, who was something of a prodigy, and his sisters a progressive education. As a teen Pascal wrote a paper on the geometry of cones and designed a mechanical calculator for his tax collector father – it was the first in Europe and a precursor, at a stretch, to the computer. (This is one of the reasons for Tomlin’s hyperbolic book title: ‘The Man Who Made the Modern World’.)

He performed innovative experiments on vacuums and pressure, and pioneered hydraulics – the reason why the measurement of pressure – the ‘pascal’ – is named after him. In fact, Tomlin notes that Pascal’s measurement of atmospheric pressure on a mountain is claimed to be the first proper scientific experiment.

Although Pascal was taught that science and theology were compatible – both pointing to an ordered, created world – he was different to Descartes, who prioritised logic. Pascal didn’t write off the physical world, and his scientific experiments showed his interest in evidence. At the same time, he advocated for the mystery at the heart of religious experience. He was a man torn between, or at least balanced between, scientific and spiritual pursuits.

Pascal’s religiosity was, writes Tomlin, a reaction to the philosophies of both Descartes and Montaigne, who Pascal thought were both, in their own ways, too focussed on the self. Pascal had a religious experience in Paris, not unlike that of Aquinas or Saint Paul, at the time his sister entered a convent. This was not so much a conversion as an intensification – one that was described on slips of paper that he carried sewn into his jacket, discovered only after he died – the famous ‘Pensees’ (‘thoughts’). Central to his religious vision is that one can’t reason one’s way to God.

Pascal criticised the compromised position of the church in its Jesuit and Renaissance iterations. He wanted a total dependence on God, which he saw in the early church, but which to his critics, in Catholic France, smelled of Calvinism (because it seemed to reduce people’s ability to choose God). For Pascal, God was not just a great mathematician or prime mover, and not just a granter of prosperity, but a filler of the heart. Understanding God is all about being struck by love (like a romantic relationship but mystical), not coming to God through reason, but not antagonistic to it. One doesn’t need to follow all the theological controversies Tomlin describes (though he makes them quite readable) to understand that Pascal very cleverly gets to the heart of the matter: that living a virtuous life is not about willpower but about a divinely changed heart that desires the good. Pascal was enough of a deep thinker to know that deep thinking is not enough – we humans are emotional creatures too.

Pascal was sceptical of natural theology, arguing instead that God is found hidden in the figure of Jesus Christ, who is not a military figure like Muhammad, nor even the Messiah figure suggested in the Old Testament. And this God must be revealed by looking, as in aspects of science, but from within Christianity. He didn’t conclude that there was no evidence for God, but that theology is a different field of inquiry. For Pascal, one knows God not through experiment or reason but through testimony, an appeal to the emotions, prefiguring the arguments of the likes of G K Chesterton and C S Lewis.

All this is the context from which to understand Pascal’s argument of ‘the Wager’, according to Tomlin, a former Anglican bishop and therefore unsurprisingly sympathetic to Pascal’s spiritual orientation. Pascal was a pioneer of probability theory, and he applies this to religious faith, but the Wager is not an argument for the existence of God that is meant to convince unbelievers. The Wager is meant more as a thought experiment to illuminate the nature of what faith is exactly, aimed at the agnostic and intending to suggest that it’s not reason that encourages or stops belief. The Wager shows Pascal’s attitude to reason: it is good in itself but only takes you so far.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.