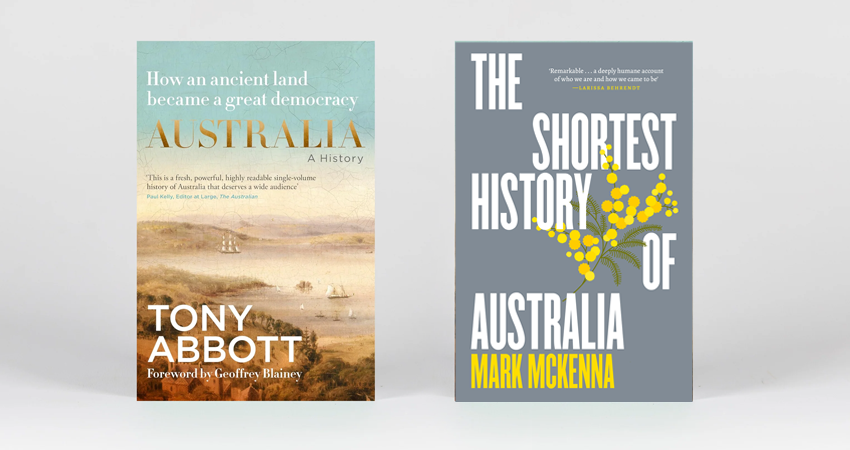

Reviews: The Shortest History of Australia, Mark McKenna, Black Inc, Australia: A History, Tony Abbott, HarperCollins

If you are thinking of reading Tony Abbott’s history of Australia, allow me to humbly suggest an alternative. Abbott says in the introduction to his book that it is one that ‘should never have been needed’. It isn’t needed. He means that current narratives need a correction from too much gloom and doom and distortion. But his is the same old narrow story, whereas recent historians have revealed the complexities of history, listening to voices previously silenced and peering at the reality behind the narratives told by the winners.

Mark McKenna writes that most Australian history narratives are ‘rise and rise’: aside from a few bumps along the way, it’s a story of progress, and this description fits Abbott’s – ‘settlement’, gold, Anzacs, postwar prosperity – to a tee. Abbott suggests that even Indigenous Australians – considering they are now accepted as citizens – should be proud, from viewing the ‘objective facts’ [sic]. On weighing it up, Australia is a raging success. (And Paul Keating is simply ‘one-sided’ for his truth-telling in his famous Redfern speech.)

McKenna’s view is not the opposite, exactly. His view is that success was mixed, and Australia’s history is complex, such that, if we think it is a success, we should be asking ‘for whom?’ Abbott’s view is a typical simplification: for the likes of Abbott and Geoffrey Blainey, from whom Abbott takes his cue, to point out faults is to cause the house of cards to collapse. It comes down to an ultimate evaluation: is it good or bad, triumph or disaster?

Of course, for many migrants and even some Aboriginal people, contemporary Australia is a good place, but truth-telling means acknowledging that it has come at a cost, that not everyone has benefitted, and some have benefitted disproportionately. Abbott seems to see this as a propaganda, when, instead, it recognises the dark parts of our history that have been swept under the rug – these are the ‘objective facts’. (As a Catholic, it is odd that Abbott seems so reluctant to confess to past wrongs.) As well as celebrating successes, we can aim for healing, and that only happens after recognition.

Abbott sums up the long history of Indigenous Australia in about 3 pages, then it’s on to the more important matter of British arrivals, who apparently got along well with the natives and respected them, which included kidnapping them. The colony was full of ‘enlightened’ and enterprising fellows who quickly invaded Indigenous land. Unfortunately, when the original owners pushed back, the ‘graziers often overreacted’. Abbott’s upbeat take on frontier violence is that it would have been worse under the French. (This is a bit like saying you should be grateful for a punch in the mouth instead of a knife in the guts.)

It’s not that he totally ignores these things, but he cautions that we shouldn’t judge by the standards of our time. But this is undermined by his recognition that there were those back then with progressive attitudes who recognised injustices, such as William Wilberforce. And the frontier massacres that Abbott does mention were only brought to light by the tenacious ‘black armband’ historians he so disparages.

McKenna, in contrast, arranges the narrative in his book by theme rather than chronology, all revolving around the core of the long Indigenous management of the land. Rather than picturing Indigenous Australia as ‘undisturbed’ and stuck in the past, as Abbott does, McKenna writes about a dynamic culture with links to Asia and symbiosis with the land. He writes that Australia’s ‘founding lie’ is that Australia was ‘settled’. The truth is that it was ‘invaded’ and its people ‘conquered’. The early colonists described taking possession of Australia as akin to magic. They meant it positively, McKenna does not.

‘Few Australians understand how their land was won,’ McKenna writes. Colonists took land, and the government ‘gave’ land to pastoralists, whose descendants are still profiting. Granting land to ex-convicts was ‘enlightened’, but this created frontier warfare – a word used in colonial descriptions, not just today. In Tasmania, ‘settlers’ talked openly of extermination. (The Australian War Memorial nevertheless refuses to acknowledge the frontier wars.) Some colonists, and ‘humanitarian and church groups’, deplored the bloodshed but also assumed there was a kind of inevitability about it, and colonists and authorities could hold contradictory views that the land was both Aboriginal and ripe for divinely sanctioned takeover.

Because he understands the complexity of history, McKenna can agree with Abbott that the Australian penal colony was largely successful in rehabilitating and advancing convicts. (It probably helped that most convicts weren’t hardened criminals but were transported for often trivial reasons.) But, unlike Abbott, who thinks environmental concerns are a load of codswallop, McKenna is aware of the consequences for ecology. He quotes the environmental historian and farmer Eric Rolls, who wrote about how from mining to agriculture, the colonists’ approach to the environment was an unprecedented disaster conducted with unflagging enthusiasm. Mainstream Australia continues to misunderstand fire, agriculture is still based on European models, and the Murray continues to be a sick river.

Contemporary Australia, despite celebrations of the ‘bush’, sits uneasily on the land. McKenna makes the perceptive observation that while Australia has a strong beach culture, we remain isolated culturally from the South Pacific. At the same time, (non-Indigenous) Australia remains wary of the vast centre of the nation. This is probably not going to change much as recent immigrants crowd into coastal cities.

Abbott laments the postwar decline in civic ‘duty’, while celebrating that Australia has become a land of ‘little capitalists’, failing to recognise that the first might have something to do with the second. Meanwhile, he thinks contemporary failures in Aboriginal Australia are due not to the legacy of invasion but to an ‘activist class’ that focusses too much on culture (a word he witheringly puts in inverted commas) and ‘encourage[s] people to live in remote places’ (!), presumably at the expense of making Aboriginal Australians ‘little capitalists’. He bemoans, as most of us do, the sudden lack of housing affordability, which can be traced directly to one of his heroes, John Howard. He laments the recent loss of a Christian consensus, ignoring the fact that, for example, in 1901 only 40% of citizens were regular churchgoers.

A monochromatic image of a nation is shaped by leaders and, of course, the majority, but it is a mixed and ambivalent thing. Yes, Britain gave us a solid democratic model, but it also exported aggressive colonialism. There is generosity but also parochial meanness. Australia has been successful in its multiculturalism, but there is also division. The story repeats over history: (white) mainstream agony over and antagonism towards the Irish, the Chinese, Italians and Greeks, the Vietnamese, arrivals from the Middle East and Africa. And as both Abbott’s book and the recent Voice referendum show, we are still to come to terms with the reality of Indigenous dispossession, and what that means for the land’s ability to keep supporting us.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at coburgreviewofbooks.wordpress.com and is the illustrator of Thoughts That Feel So Big.